Anatomy of Tornadoes

What are Tornadoes?

Known as twisters, whirlwinds and cyclones, tornadoes are made up of a violently rotating column of air that makes contact with both the surface of the earth and a cumulus or cumulonimbus cloud. The word cyclone is used in meteorology to name a weather system with a low-pressure area that blows counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern.

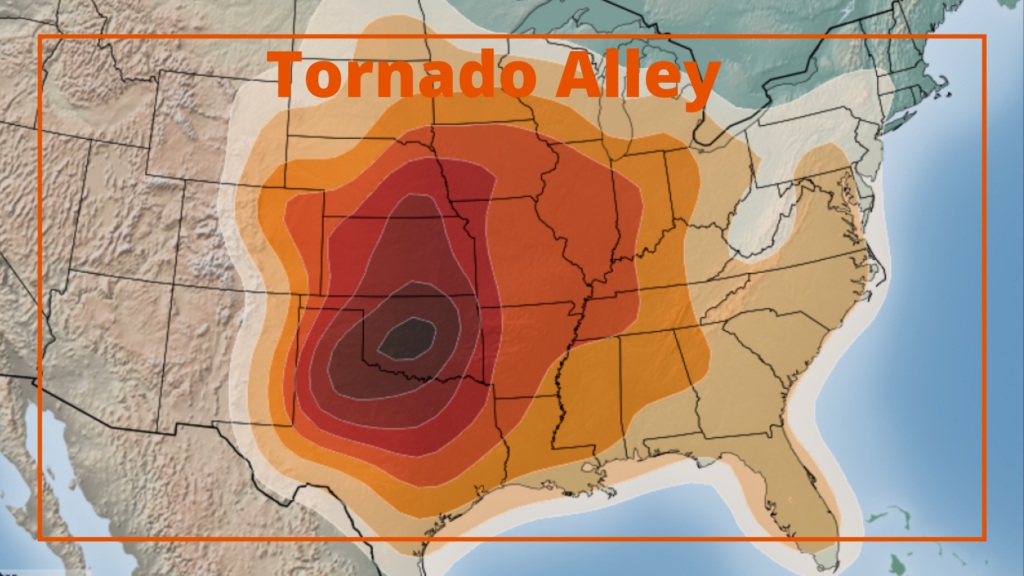

Tornado Alley

During the springtime in North America, tornadoes frequently strike fear in the hearts of mid-westerns, particularly those living in an area known as Tornado Alley.

Types of Tornadoes

Tornadoes come in a multitude of types, including multiple vortex tornadoes, tornado families, stovepipe and wedge funnels, landspouts, waterspouts and lesser tornado-like events such as gustnadoes, dust devils, fire whirls and steam devils.

Not all tornadoes are visible, but they share in common a low-pressure area caused by high wind speeds—as described by Bernoulli’s principle—combined with rapid rotation and condensation formed by adiabatic cooling, resulting in the appearance of a funnel cloud.

Tornadoes come in a wide range of shapes and sizes, and while most travel a few miles on the ground with winds less than 110 miles per hour, some of the most extreme tornadoes can reach wind speeds of more than 300 miles per hour and stay on the ground for dozens of miles.

Record Breaking Tornado Statistics

- 2004: A tornado funnel in Hallam, Nebraska clocked in at two and a half miles wide.

- 2013: A tornado in El Reno, Oklahoma holds the all-time girth record at 2.6 miles wide.

- 1925: In terms of path length records on the ground, the Tri-State Tornado of 1925 stayed on the ground for 219 consecutive miles, tearing a path through parts of Missouri, Illinois and Indiana, before “roping out,” as meteorologists call the phenomenon, when a funnel cloud finally rises off the ground and dissipates.

Measuring Tornadoes

Frequently reported by storm chasers, tornadoes can also be detected by the use of Pulse-Doppler radar, which looks for patterns in velocity and reflectivity data, such as hook echoes or debris balls.

A tornadoes strength and damage are generally reported using the Fujita Scale or Enhanced Fujita Scale, and while an F0 or an EF0 tornado barely damages trees, an F5 or an EF5 tornado can rip buildings from their foundations and severely twist or deform tall skyscrapers, making tornadoes one of the most terrifying yet awe-inspiring events in Mother Nature’s broad arsenal of naturally-occurring havoc.