Navigators of Polynesia

How was Polynesia Populated?

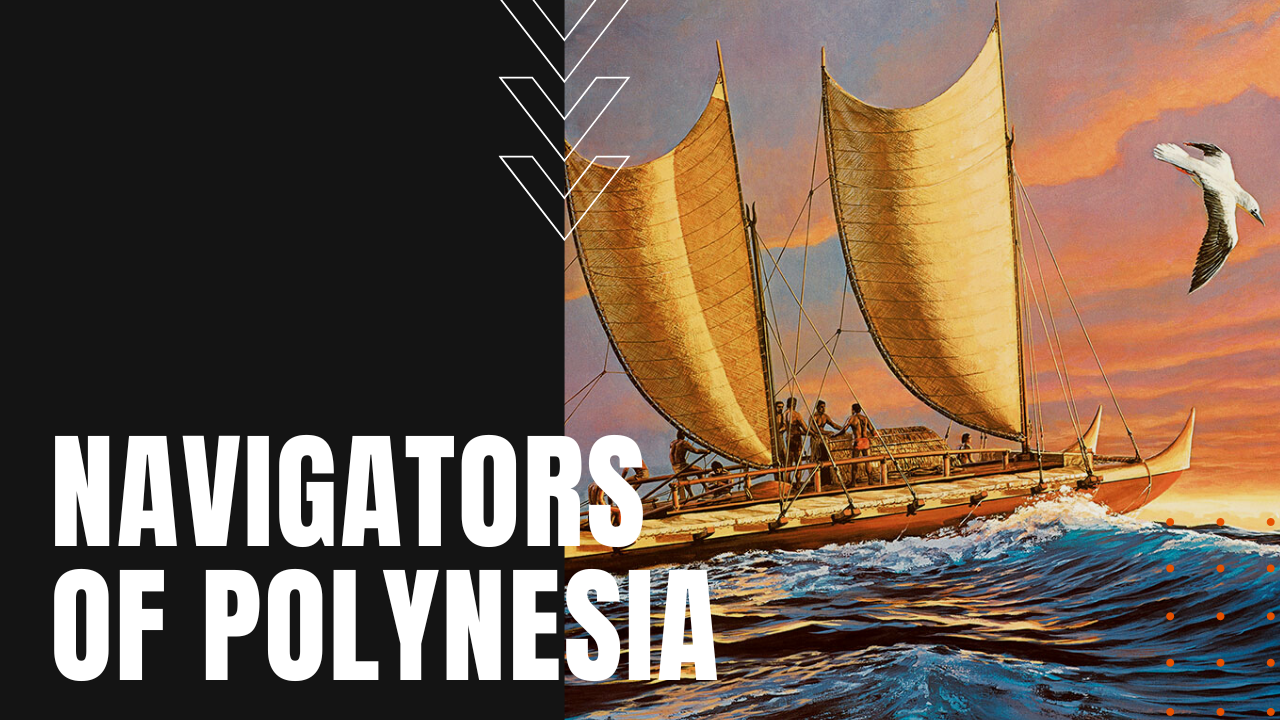

Considered one of the most courageous and beguiling achievements in human history, the peopling of Polynesia began around 800 A.D., when audacious navigators set out from Taiwan and Southeast Asia in double-hulled sailing canoes across vast stretches of open ocean, using star maps, sea swells, current and drift to make landfalls sometimes thousands of miles away.

Sailing in ocean-going canoes from 50 to 75 feet in length, groups as large as 50 people put their lives in the hands of illiterate navigators, whose knowledge was passed down from father to son.

Ancient Polynesian Navigation Methods

Using 32 memorized stars to form a sidereal or star compass, Polynesian navigators tracked their position by using a memorized sequence of stars—generally ten per night—as they rose or set against the horizon. Polynesian navigators relied heavily on an intuitive sense of ocean current and a given boat’s leeway, which is the angle a boat is drifting off the wind.

Using geographic backsights from the land they just departed, when a navigator was 5 to 6 miles offshore, they knew from passed down knowledge or personal experience that most currents in Polynesia moved east to west, although in Micronesia, they could anticipate an equatorial counter-current that ran west to east.

They also read currents by their sense of balance aboard ship, as well as wave shapes and deep water phosphorescence at night. Polynesian navigators maintained a strong sense of position by keeping their home island and other intermediate islands firmly affixed in their mind—even during gales and cloud-covered nights—employing an early navigation technique known as etak, which allowed a grandson to follow sea routes sailed by his grandfather.

Signs of Land

While finding a given island in the vast expanse of Polynesia required incredibly accurate, pre-GPS navigation techniques, Polynesian navigators were adept at identifying signs of an approaching island, most notably by the presence of sea birds that fly away from islands in the morning, while returning home near sunset, many in foraging flight paths that took them 30 to 50 miles away from land. Characteristic cloud patterns that form over islands comprised another important landfall technique, while an increase in deep water phosphorescence could help them identify a land mass from as far away as 80 to 100 miles, making the peopling of Oceania, one of the most enduring achievements in the history of man.