Plagues of San Francisco

In the summer of 1899, a ship sailing from Hong Kong arrived into San Francisco Bay with two active cases of bubonic plague onboard, prompting health officials to quarantine the infected on Angel Island. After customs agents made a second search of the ship, 11 stowaways were discovered, and when two of the un-ticketed passengers escaped their detention, their bodies were later found in the Bay—both testing positive for bubonic plague.

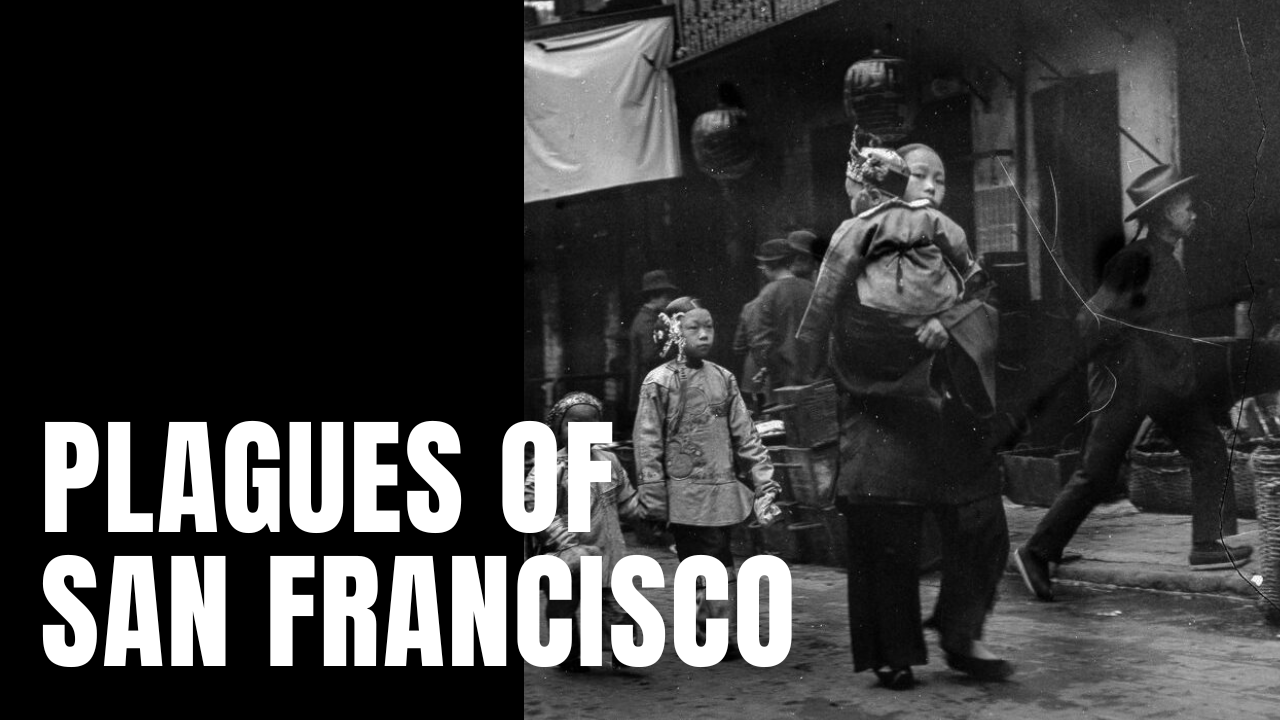

Fake News

Despite the potential for a looming disaster, California Governor Henry Gage labeled health department concerns as fake news, unwilling to risk the state’s heavy economic reliance on outside trade, which in turn enabled the first wave of a plague pandemic to spread throughout the Bay Area from 1900 to 1904. Given the anti-Asian, racist tenor of the day—some 18 years after Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act—residents in Chinatown took the brunt of the blame for the rising pandemic, while for his callous disregard and coverup, Gage was voted out of office in 1902.

A Deadly Outbreak

By the time the outbreak was contained in 1904, 121 cases had been identified, with 119 fatalities. Two years later, much of the city’s urban center was destroyed by the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906, driving thousands of San Franciscans into homeless encampments during the rebuild process, which proved to be a field day for scavenging rats. For a disease caused by the transmission of the Yersinia pestis bacteria from rats to humans, borne by the Xenopsylla cheopis flea, the city’s tragic natural disaster led to a second wave of plague outbreaks in the summer of 1907, prompting city officials to undertake a rat eradication campaign that cost city residents over two million dollars, or $62 million in today’s currency.

Another Bad One

After health officials proved without a doubt that the second outbreak occurred outside of Chinatown, in June of 1908, 160 fresh cases of plague had been identified, with a reduced mortality rate compared to the first outbreak of just 78 lives. During the Bay Area’s second outbreak of plague, health officials pointed to infected immigrants from Europe, while this time around, the transmission vector was pinned on the lowly California ground squirrel, which remains a virulent carrier of the disease to this day. Thanks to the cold-hearted indifference of the state’s leading politician, the ousted governor’s initial denial gave the dreaded and quite deadly bubonic plague its first foothold in America, leading to sporadic outbreaks in the years to come, making the San Francisco plagues of the early 20th century, a potential powder keg for pandemic loss.