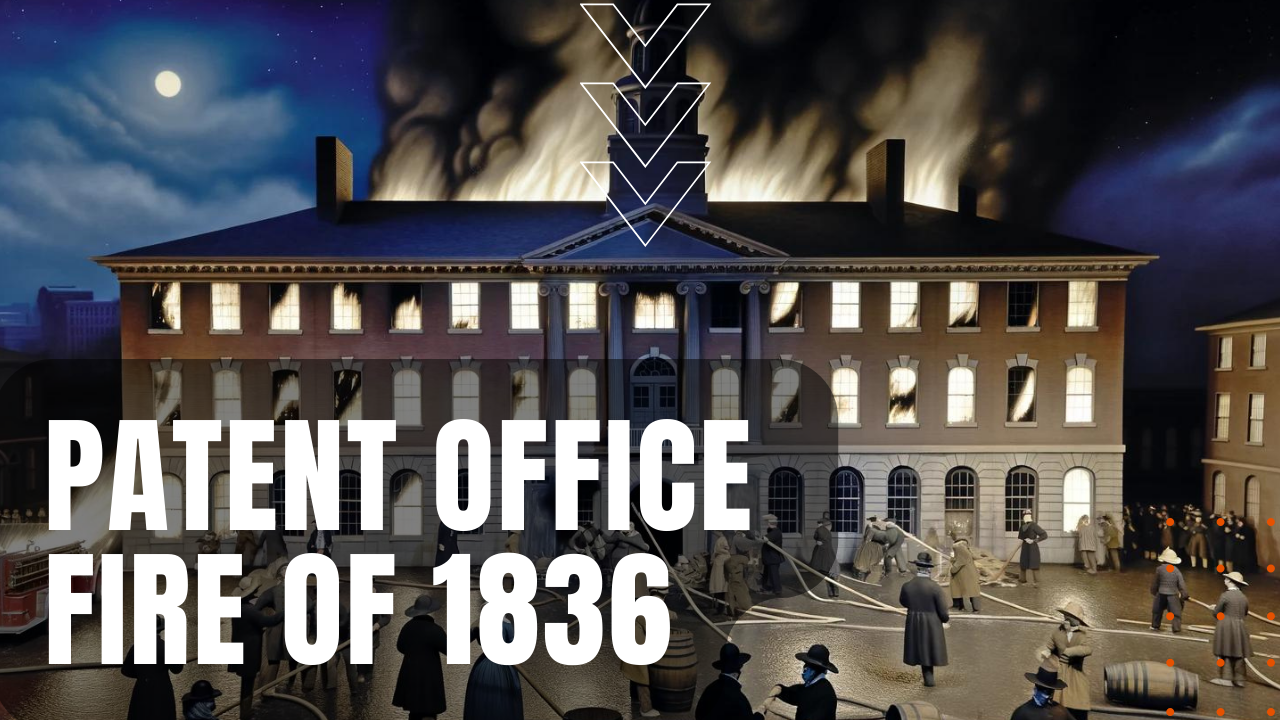

The Patent Office Fire of 1836

After Congress purchased the unfinished Blodgett’s Hotel in 1810, to house the Post Office and the Patent Office, during the War of 1812, when the British burned nearly all government buildings in the District of Columbia, Patent Office Superintendent Dr. William Thornton—who had previously designed the first U.S. Capitol—convinced officers of the British expeditionary force to spare the patent office. Eight years later, fully aware of the building’s susceptibility to fire, Congress funded a slate roof for the patent office, purchasing a fire engine, a forcing pump and 1,000 feet of fire hose, which in turn caused the district’s dispirited volunteer fire department to disband due to a lost sense of purpose.

Poor Fire Prevention Practices

As bad luck would have it, fire broke out in the patent office at 3:00 A.M. the morning of December 15th, 1836, in what was later determined to be the basement of the building, where patent office employees stored their firewood. Like many bad decisions that lead to monumental disasters, postal employees also disposed of their hot ashes in the same locale, leading to the unintentional ignition of the patent office’s firewood supply. Lacking firemen to fight the fire, townspeople attempted to put out the blaze by running a bucket brigade, abandoning their efforts when the building turned into an overwhelming inferno. The fire destroyed all 9,957 patents, 9,000 drawings and 7,000 related patent models dating back to the first U.S.-issued patent on July 31st, 1790, including, ironically, the original patent for the fire hydrant.

Too Little Too Late

Another stroke of bad luck was the fact that the fire occurred while the Patent Act of 1836 was working its way through Congress, which required that patent applications be examined prior to a patent grant. After the fire, an amendment to the act was added the following year, which required the submission of two copies of drawings or models, one for safekeeping in the patent office, while the second was attached to a granted patent, which was subsequently mailed to the applicant. All patents prior to the fire were later listed as X-Patents, and while Congress apportioned $100,000 to restore the lost patents—some five million in today’s currency—after the majority of the money had been spent, only 2,845 patent records had been restored, making the patent office fire of 1836, a massive setback in a nation’s thirst for innovation.