History of Miranda Rights

If you’ve ever watched a police procedural or had the bad fortune of being arrested by police, the words,

“You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can, and will, be used against you in court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford one, one will be appointed to you.”

Miranda rights

Miranda v Arizona

These words became a police procedural of their own on June 13th, 1966, when the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision on Miranda v. Arizona, establishing a new law enforcement mandate that all criminal suspects must be advised of their rights before interrogation.

The Miranda Rights decision by the Supreme Court came about when on March 2nd, 1963, an 18-year-old Phoenix woman alerted police that she had been abducted by a man, who raped her in a secluded patch of desert outside of town. Despite multiple inconclusive polygraphs on the victim, police tracked a license plate number to a similar model car reported by the victim, arresting Ernesto Miranda, who had a prior felony as a peeping tom.

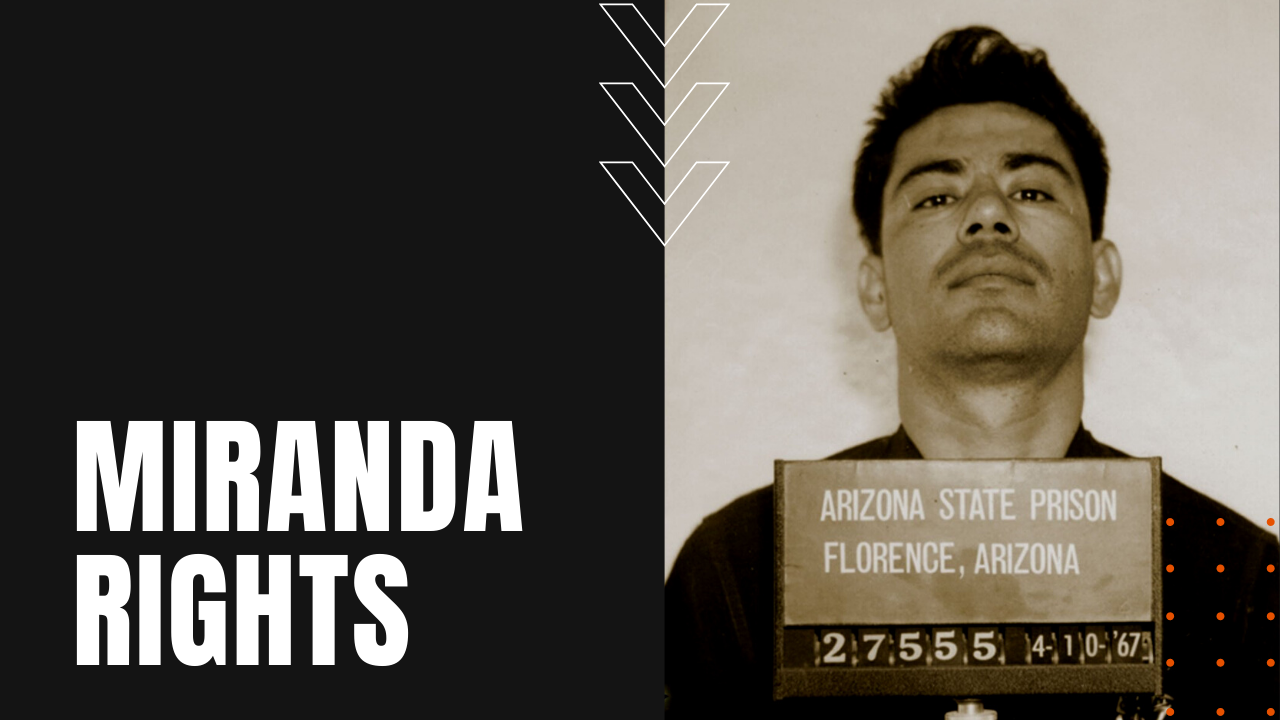

Despite the woman’s failure to identify Miranda in a police lineup, Miranda confessed to the crime under heavy police interrogation, which he later recanted. When Miranda’s case went to trial, his appointed defense attorney failed to call any witnesses during the ensuing trial, resulting in Miranda’s conviction and imprisonment at an Arizona State prison.

After the American Civil Liberties Union took up Miranda’s appeal, the Union’s claim that his confession was false and coerced made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where his conviction was overturned, at the same time cementing Miranda Rights into law. Despite the Supreme Court’s decision, Miranda was retried and convicted in October of 1966, remaining in prison until his release in 1972. Four years later, Ernesto Miranda was stabbed to death in the men’s room of a bar after a poker game.