Leap Day’s Gregorian Calendar History

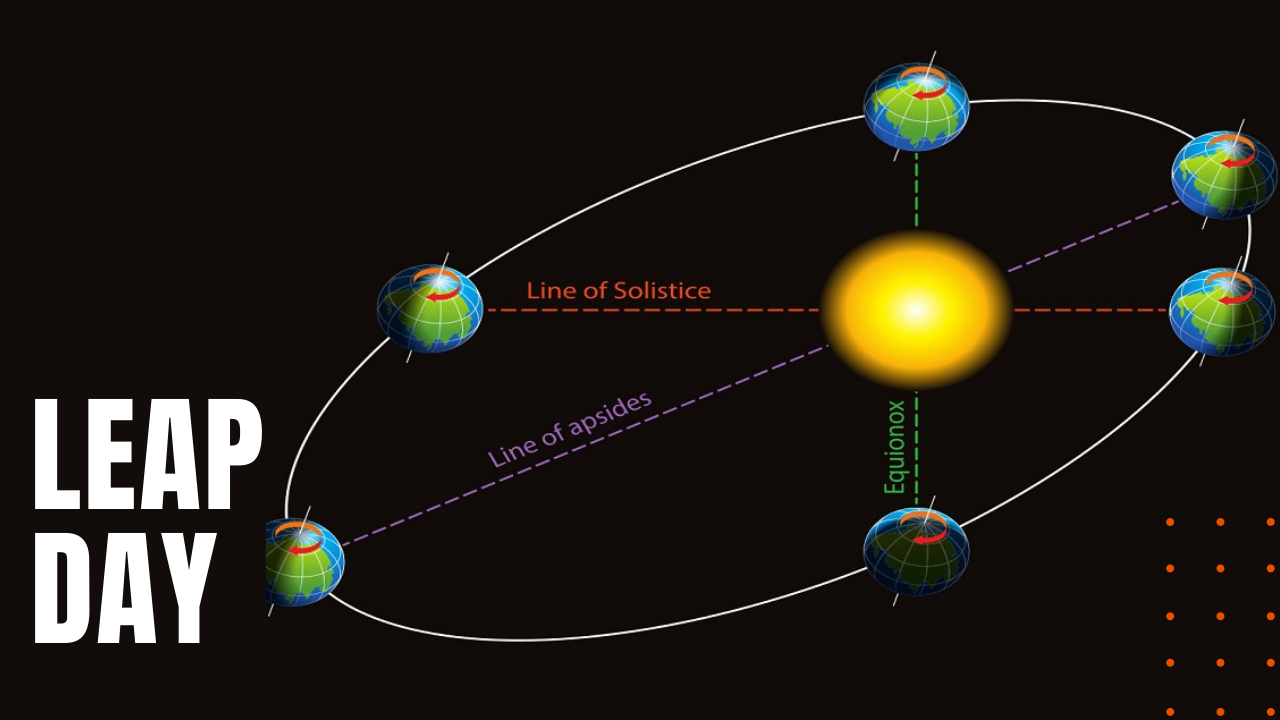

Every four years in the Gregorian calendar, a day is tacked on to the end of February, in order to synchronize the calendar year with the solar year, since in actuality, it takes the earth 365.2421 days to orbit the sun.

The extra quarter of a day doesn’t seem like it would make much of a difference, but since the cycle of the seasons matches up with Earth’s orbit around the sun, every four years the seasons would move by one day, which on the surface sounds inconsequential, but after a few hundred years of ignoring Leap Days, the days of the Gregorian calendar would become completely out of sync with the seasons. Halloween would be in Spring, and Christmas would be in the middle of Summer.

Julian vs Gregorian Calendar

The need for a Leap Day was known as far back as ancient Egypt, but the practice of a Leap Day did not begin until the reign of Julius Caesar, when in 46 BCE, the Julian calendar was first introduced. With the Julian calendar, the seasons would still shift, but the year only moved one day every 128 years, instead of one day every four years. Even so, by 1582, the Julian calendar was ten days out of sync with the seasons, until Pope Gregory the 13th introduced the Gregorian calendar.

Any year that can be divided by four is a Leap Year, unless that year can be divided by 100, in which case it’s not. To add to the complexity, if a year can be divided by 400, that too makes it a Leap Year. For instance, the years 1700, 1800 and 1900 were not Leap Years, while 2000 was. By using the Gregorian calendar, the year will stay aligned with the seasons for almost 8,000 years without an additional correction, making old people born on Leap Day, some of the youngest people on earth.