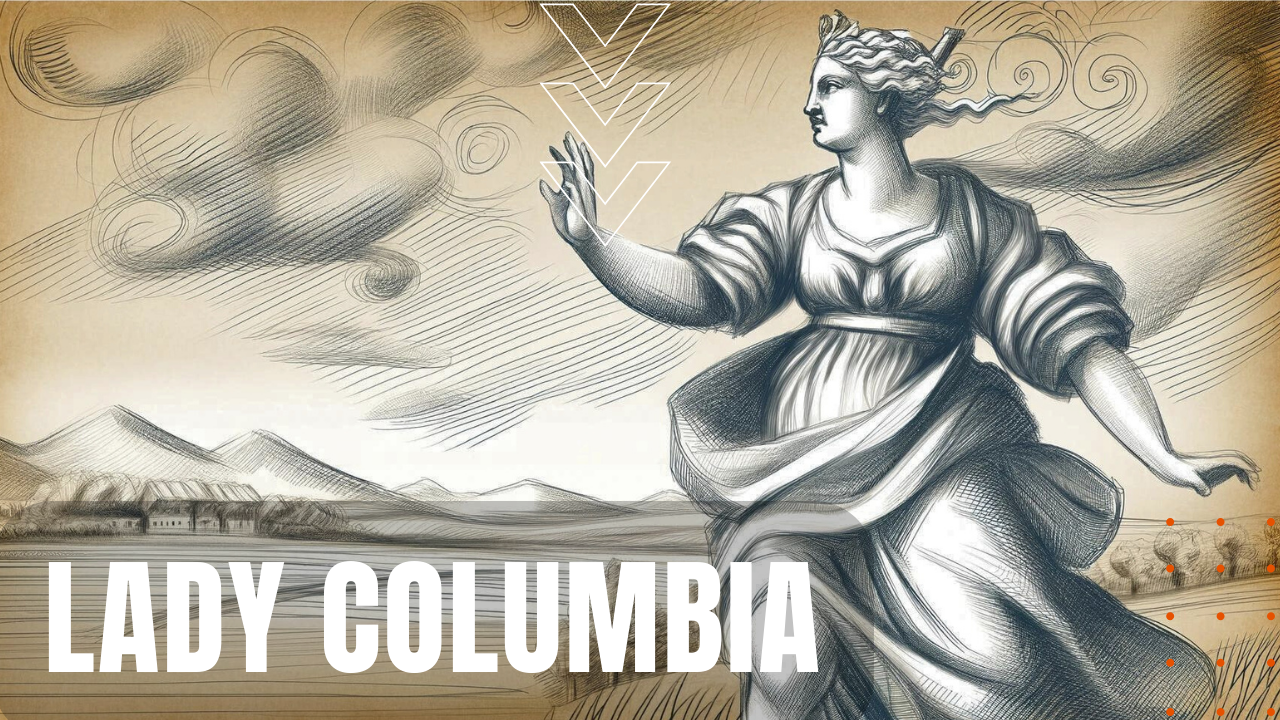

Lady Columbia

Before the creation of Lady Liberty as we know her today, the first and longest-ruling mascot of the United States found her roots in poems and sermons that referred to her as “Columbina,” captured best by Samuel Sewall of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, when he wrote in a 1687 essay how Columbina was the emblem of the “New Heaven” of the American colonies. By the early 18th century, Columbina had morphed into the more diminutive Lady Columbia, and as her image spread through the colonies, her neoclassical goddess image, replete with a sword, an olive branch and a laurel wreath became enduring metaphors for justice, peace and independence.

Ode to Columbia

Serving first as a nurturing mother figure during colonial times, when the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, Lady Columbia morphed yet again into that of an avenging angel, prompting African American poet Phillis Wheatley to send General George Washington an ode to Columbia, where she urged Washington to “Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side, Thy ev’ry action let the goddess guide.” Over the course of the war, Lady Columbia became a rallying cry for strength and perseverance, leading lawyer and poet Joseph Hopkinson to write in 1798, “Hail Columbia, happy land, Hail, ye heroes, heav’n-born band, Who fought and bled in Freedom’s cause.”

First Unofficial National Anthem

Hopkinson’s poem would soon be set to music, becoming the nation’s first unofficial national anthem throughout the 19th century. During the War of 1812, Lady Columbia frequently joined forces with Uncle Sam, who together represented the fierce embodiment of American independence, while during the years of westward expansion, Lady Columbia became the symbol of American manifest destiny. Her image was frequently used by both Northern and Southern cartoonist in the years leading up to the Civil War, including a cartoon depicting Lady Columbia spanking politician Stephen Douglas for proposing that laws governing slavery should be decided by individual states.

Displacement on the Horizon

Her image also became emblematic during the high water years of European immigration into the U.S., becoming a figurehead behind a patriotic movement called Columbianism, which helped millions of immigrants develop a common American identity. Lady Columbia’s long reign ended upon the dedication of the Statue of Liberty on October 28th, 1886, where a less neoclassical figure marked the nation’s embrace of modern times, making Lady Columbia, a bygone symbol of American strength and independence.