Internment of Japanese Americans During WWII

After Japan’s unprovoked attack on American naval forces at Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese sentiment resonated throughout North America, prompting Western Defense Command leader, General John L. DeWitt to lobby Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Attorney General Francis Biddle for the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Penning a report brimming with known falsehoods about acts of sabotage by Japanese Americans, DeWitt’s initial plan called for the internment of German and Italian-Americans as well—a sentiment which proved to be overly offensive to most lawmakers in Washington.

Executive Order 9066

Despite Biddle’s repeated pleas to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that such mass violations of civil rights was completely unnecessary, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19th, 1942, with the express intent of preventing espionage on American soil.

FDR’s order would lead to the forced internment of some 120,000 mostly American citizens for the remainder of the war years. After internment efforts kicked off with an abundance of logistical chaos, a civilian organization known as the War Relocation Authority was established in March of 1942, headed initially by Milton S. Eisenhower of the Department of Agriculture, who resigned three months later in protest of what he believed to be the incarceration of innocent American citizens.

1/16th Japanese Rule

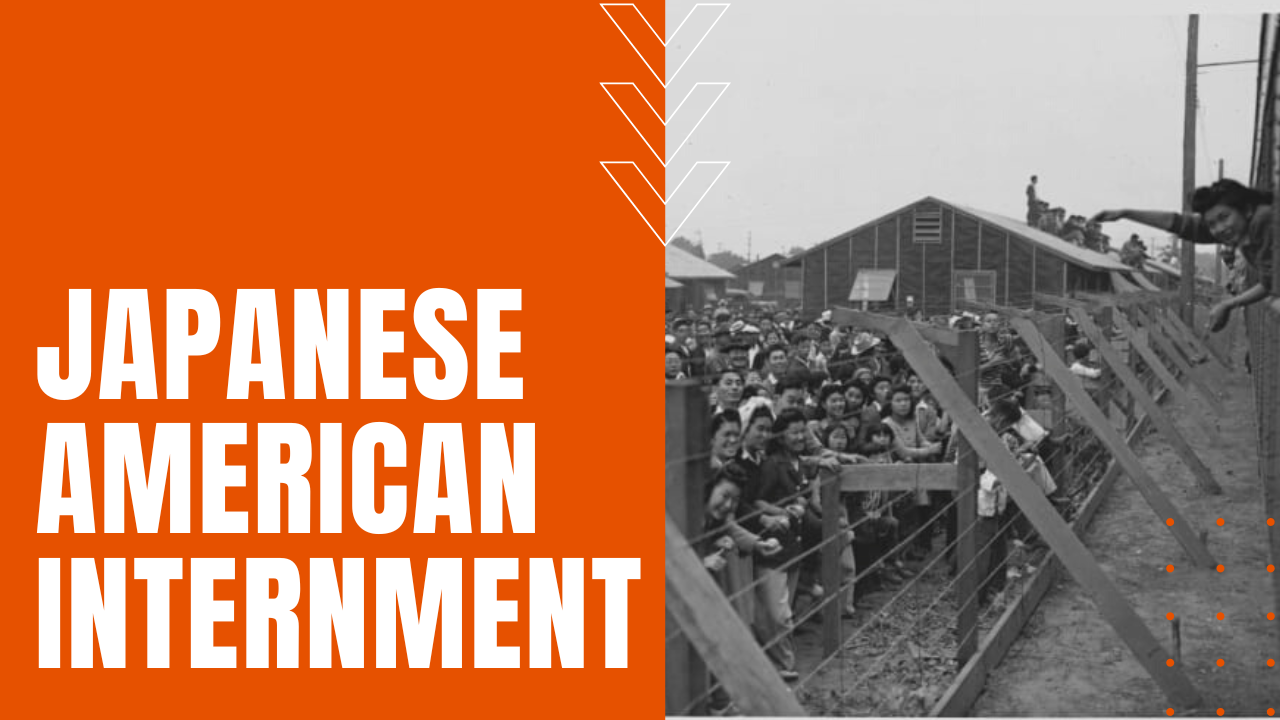

As internment efforts intensified, anyone of at least 1/16th Japanese ancestry was given six day’s notice to dispose of real estate and belongings, entering West Coast “Assembly Centers,” before moving into 10 “Relocation Centers” known as “Wartime Residences.”

The majority of these resident centers were little more than reconfigured fairgrounds, racetracks and livestock pavilions, which were hastily converted from horse stalls or cow sheds, into barrack-style living quarters and communal eating areas with substandard sanitation. Interned residents were encouraged to work for pay not to exceed that of an Army private, in jobs ranging from healthcare, education and agriculture, while each interned community became towns of isolation, replete with schools, a post office and cordoned-off land for growing crops and raising livestock.

After Japan’s surrender on September 2nd, 1945, the last Japanese internment camp was closed in March of 1946, foregoing any apology by the federal government until President Gerald Ford officially repealed Executive Order 9066 in 1976. Twelve years later, Congress issued a formal apology by passing the Civil Liberties Act, which awarded some 80,000 surviving internees war-related reparations of $20,000 each, making Japanese internment camps, yet another stain on America’s disgraceful racist past.