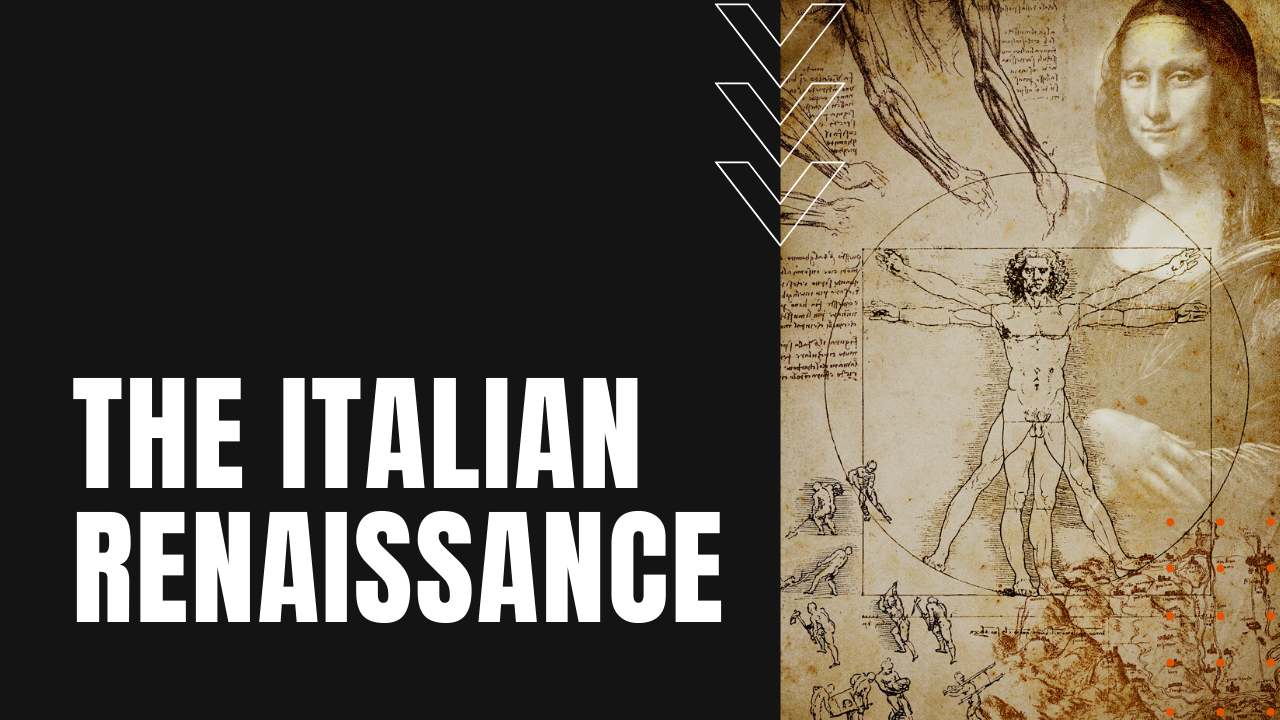

Italian Renaissance: Art, Science, and Humanism in Florence

Toward the end of the 14th century, Italian intellectuals began to declare that Italy and much of Europe had transitioned into a new age of human awareness. Gone were the brutish and unenlightened Middle Ages, replaced by a period of rebirth and growth in literature, art, culture and science.

Spanning into the 17th century, Renaissance thinkers shared a common theme book, most notably a new humanistic belief that man was at the center of his own universe. 15th century Italy was unique to Europe, with each city-state practicing its own and quite diverse forms of government.

Florence, Italy: Birthplace of Italian Renaissance

Considered the birthplace of the Italian Renaissance, Florence was an independent republic, whose merchants and banking interests were third in Europe behind London and Constantinople. Wealthy Florentine businessmen gave financial support to artists and intellectuals, which allowed their recipients to create new art and ideas without the pressing need for ordinary employment.

They traveled around Italy and the continent, finding new appreciation in ancient Greek and Roman texts, all the while shunning the Holy Roman Church in exchange for humanism. Many focused their energies on the laws of nature and the physical world around them, prompting artists such as Leonardo Da Vinci to create detailed scientific studies in such diverse subjects as flying machines, submarines and human anatomy.

Galileo Galilei

During the Renaissance, scientist and mathematician Galileo studied a broad range of subjects, from gravity to astronomy, discovering that the earth and other planets in the solar system circled the sun, rather than an earth-centric model preached by the Catholic Church.

For his heresy against the teachings of Christianity, Galileo was arrested under threat of torture and death, yet he refused to recant or give in to the church’s dogmatic misconceptions. When Galileo died in 1641, he was still under house arrest—not to be pardoned by the Catholic Church until 1992.

Nearing the end of the 15th century, Italy was besieged by a steady procession of wars, as England, France, Spain and the Holy Roman Emperor vied for control of the wealthy peninsula. At the same time, the Catholic Church became mired in scandal and corruption, diverting public attention to its misdeeds with a long and violent crackdown on religious dissenters. In 1545, the Council of Trent officially imposed the Roman Inquisition, which increased the prosecution of heretics, bringing about an abrupt end to humanism and the Italian Renaissance.