A Brief History of Weather Forecasting

Almanac Weather Predictions

For centuries, Americans considered weather events to be God’s will or explainable by folklore nostrums such as “red sky and night, sailor’s delight, red sky at morn, sailors forewarn,” and while the Farmer’s Almanac began predicting weather in 1818 by a secret formula still used to this day, beginning in 1848—less than two years after its inception—the Smithsonian Institution set out to make weather forecasting more like a science than a handful of anecdotal and quite random observations.

Crowdsourced Weather Observations

That’s when the first secretary of the Smithsonian, Joseph Henry, came up with an early concept in crowd-sourcing when he sent thermometers, barometers and rain gauges to 150 volunteers around the nation, who sent daily weather report telegrams back to Henry, which allowed the Smithsonian to compile the first national weather map.

The map was displayed daily on the National Mall, which fascinated tourists and Washingtonians alike. Despite this early step forward in weather reporting, at first the system had little impact on pioneers heading west, including the 42 members of the Donner Party who perished in an early blizzard in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

As the number of weather reporting volunteers rose to over 600, Smithsonian analysts began to cobble together predictive models, for when a storm was reported over the Denver area, they could quickly and quite accurately predict the approach of bad weather as the storm system pressed east over Chicago and New York.

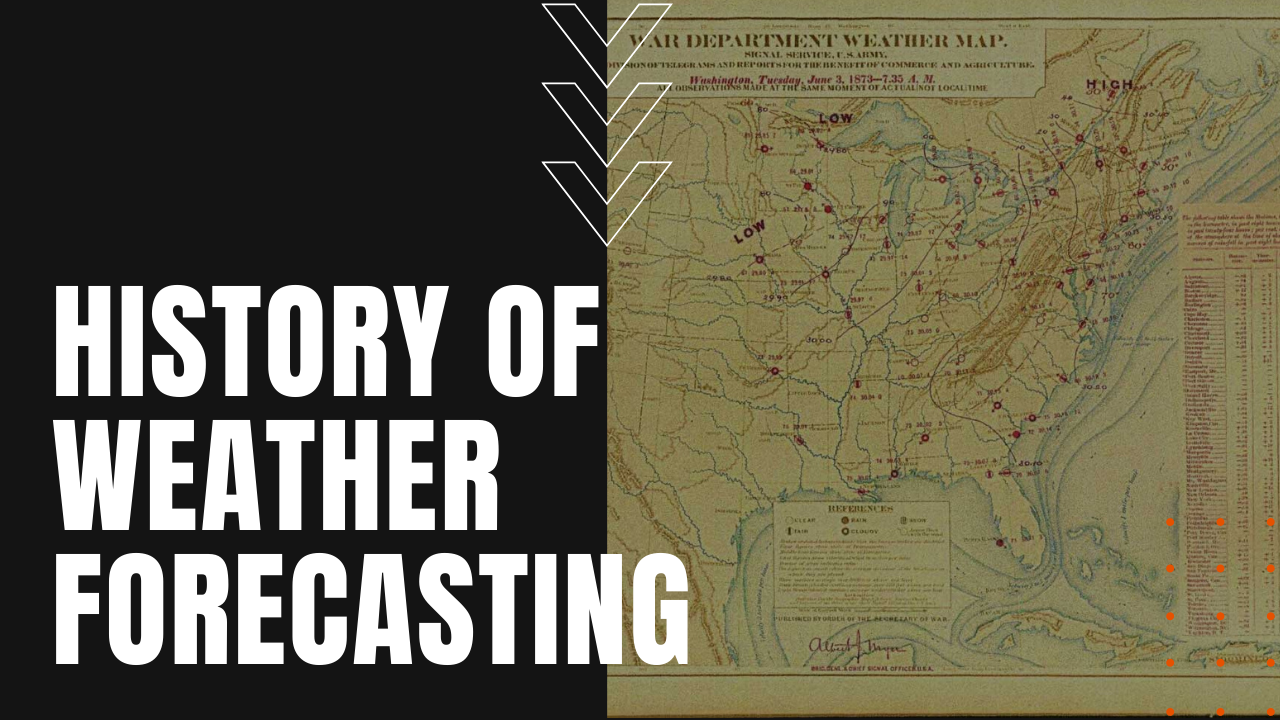

Sometimes, however, the predictive data failed to reach parts of the U.S. in time, such as a four-day gale in 1869 that witnessed the loss of 97 ships on the Great Lakes. In the aftermath of the tragedy, President Ulysses S. Grant signed a resolution into law, creating the Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce, which in turn saw the Smithsonian’s fledging weather service moved over to the U.S. Army.

National Weather Service

The Army’s weather service was soon able to provide increasingly-accurate predictions 24 hours in advance of approaching weather, which would later evolve into the National Weather Service inside the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, making members of the upstart Smithsonian Institution, some of the earliest weathermen in the nation.