History of Labor Day

During the Industrial Revolution of late 19th century America, adult and child laborers as young as six years old, toiled 12-hour days in mines, factories and mills, oftentimes in filthy, hazardous environments for pathetically low wages. Abused workers soon fought back with the rise of labor unions, leading to strikes and protests that frequently ended in violence.

A Nation Stunned

The Haymarket Riot of 1886 stunned a nation when policemen and workers were killed, while an 1894 boycott led by Eugene Debs and employees of the Pullman Palace Car Company crippled railroad traffic throughout the nation. In an effort to end the Pullman strike, the federal government ordered troops into Chicago—the very heart of the protests—igniting a wave of worker riots that ended in the deaths of more than a dozen protesters.

A Healing Gesture

In an attempt to heal the divisions between American workers and the federal government, Congress pasted a bill that made Labor Day a legal holiday, which was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland on June 28th, 1894, and while the true founder of Labor Day has yet to be identified, many credit American Federation of Labor cofounder, Peter J. McGuire, while others point to Central Labor Union secretary Matthew Maguire.

Symbolic End of Summer

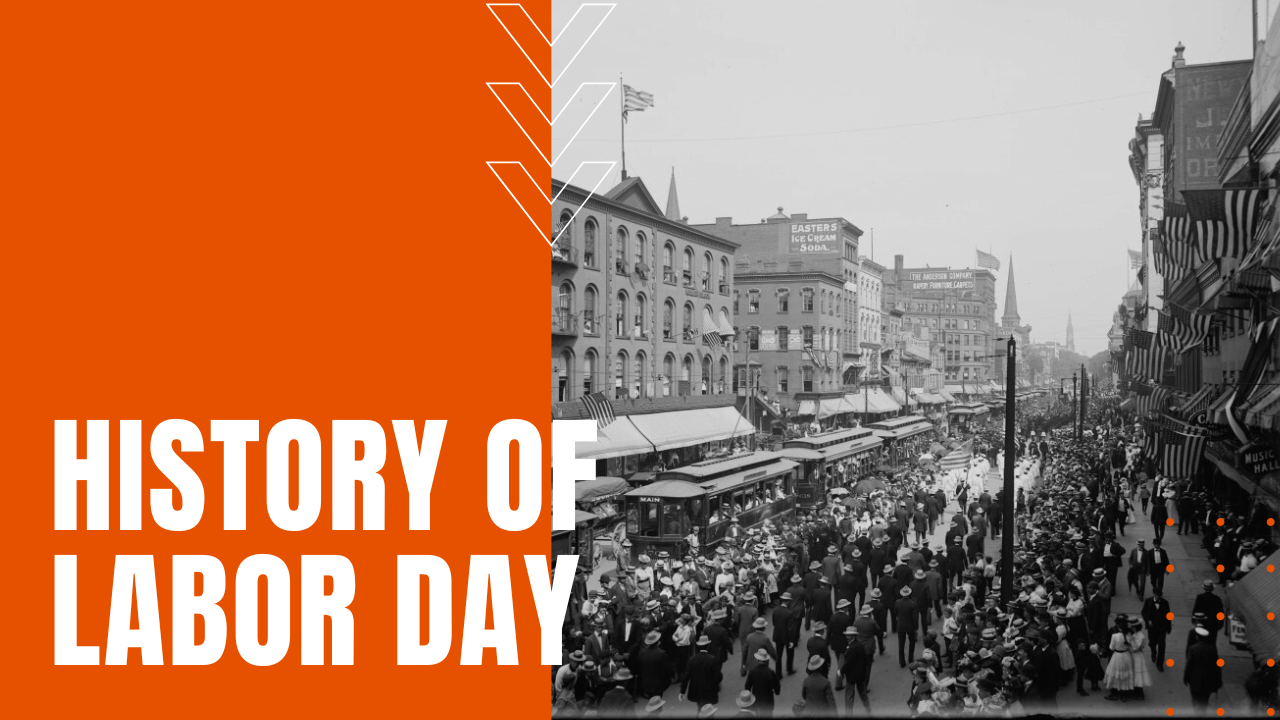

Today, Labor Day is celebrated in cities and towns across America on the first Monday of September, celebrating the proud accomplishments of American workers with parades, barbecues, picnics and fireworks displays. The day also stands as the official end of summer for children and young adults, ushering in a return to classrooms after the blissful days of summer vacation, making Labor Day, one of the happiest days for parents everywhere.