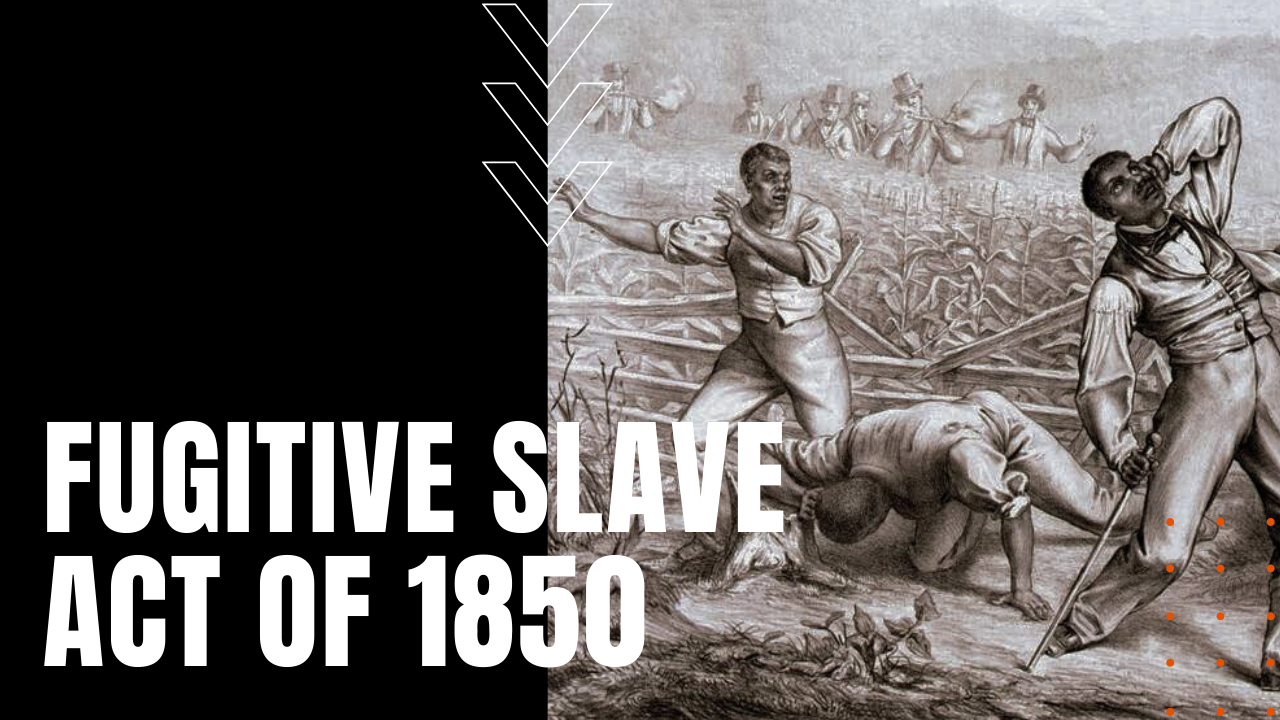

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

Beginning as early as 1643, fugitive slave laws began dotting colonial law books, including a 1705 law in New York designed to prevent runaway slaves from escaping to freedom in Canada, while Maryland and Virginia passed laws that offered bounties for the capture and safe return of runaway slaves. Yet by the start of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, most Northern states had abolished slavery entirely, obliging Southern politicians attending the convention to insist on a “Fugitive Slave Clause” to the U.S. Constitution, under the fear that free states would become a constitutional safe haven for runaway slaves.

A Replacement Act

After the Fugitive Slave Clause was replaced and bolstered by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which gave bounty hunters the right to apprehend runaway slaves in free states, plus imposed a $500 fine upon anyone harboring and abetting a fugitive slave. As part of Henry Clay’s now-infamous Compromise of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act of that same year was one of several bills intended to silence rising calls from Southern legislators to secede from the United States.

Abolitionists Forced to Capture Runaways

The new law compelled Americans to actively assist in the capture and safe return of runaways, while denying contested runaway slaves the right to a jury trial, at the same time increasing the penalty for harboring or abetting a fugitive slave from $500 as set by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 to $1,000, plus an additional penalty of six months in jail. Much like its earlier predecessor, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 faced instant criticism and pushback by a growing legion of anti-slavery activists, leading states like Vermont and Wisconsin to pass laws intended to nullify the federal mandate, at the same time doubling down on assisting runaway slaves, which saw activity in the Underground Railroad reach its peak years during the 1850s.

Abolitionist Resistance

Given such high levels of resistance and opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, by 1860, a mere 330 runaway slaves had successfully been returned to their Southern masters, despite the law’s persistence even after the start of the Civil War. Finally, on June 28th, 1864, Congress repealed both Fugitive Slaves Acts from federal penal code, making the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the final Hail Mary of compromise before a nation went to war with itself.