Freedom Summer: Black Voter Registration, Rights and Murder

After Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial, the Jim Crow South remained staunchly segregated—especially at the voting booth—where segregationist lawmakers instituted poll taxes and literacy tests intended to stymy Black American’s constitutional rights. Most glaring was Mississippi, where only 7 percent of the state’s eligible Blacks had successfully registered to vote.

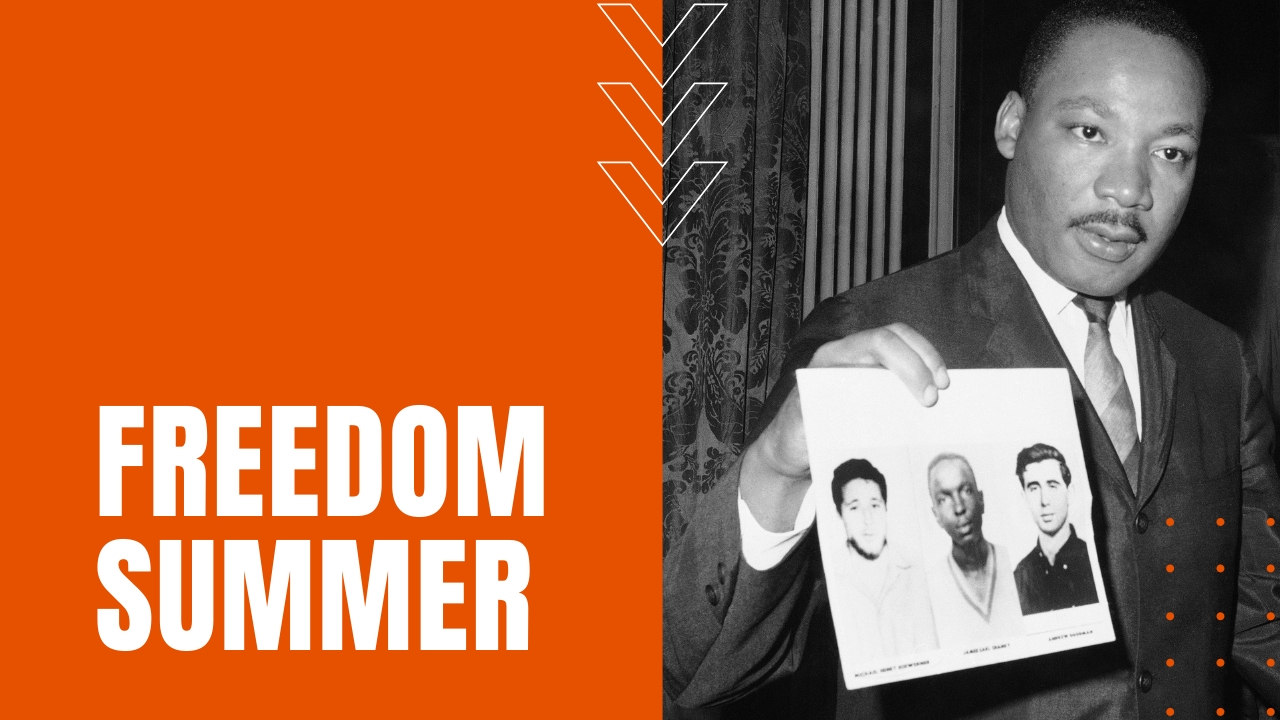

Freedom Summer Murders

Calling for civil rights activists to descend on Mississippi with the intent of registering Black voters, Mississippi Project Director Bob Moses insisted on “nonviolence in all situations,” however when the first 300 volunteers arrived on June 15th, 1964, two white students from New York, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, and local Black activist James Chaney quickly disappeared during a visit to Philadelphia, Mississippi, where they had gone to investigate the burning of a Black church.

Despite this quite troubling development, the volunteers pushed ahead with their registration efforts, receiving pushback and violence at almost every turn. Six weeks later, the badly beaten and bullet-riddled remains of the missing volunteers were recovered, killed by a Ku Klux Klan lynch mob that had the full protection and support by local police.

Results From Freedom Summer

National and international outrage would follow, citing zero federal protection and a slow investigation by local and authorities, the FBI and 400 Navy sailors. While Freedom Summer did little to increase Black voter participation—a mere 1,200 successful registrants out of 17,000 attempted tries—public outcry combined with the 1964 Democratic National Convention, where delegates from the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party were refused entry. The two events helped to persuade President Lyndon Baines Johnson and congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed segregation in public places while banning employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

Next would come the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed racial discrimination voting laws in the segregated South. Of the eighteen white men suspected of being involved in the brutal murders, only eight were charged. Seven would eventually be convicted, receiving relatively minor puppet sentences for their crimes.