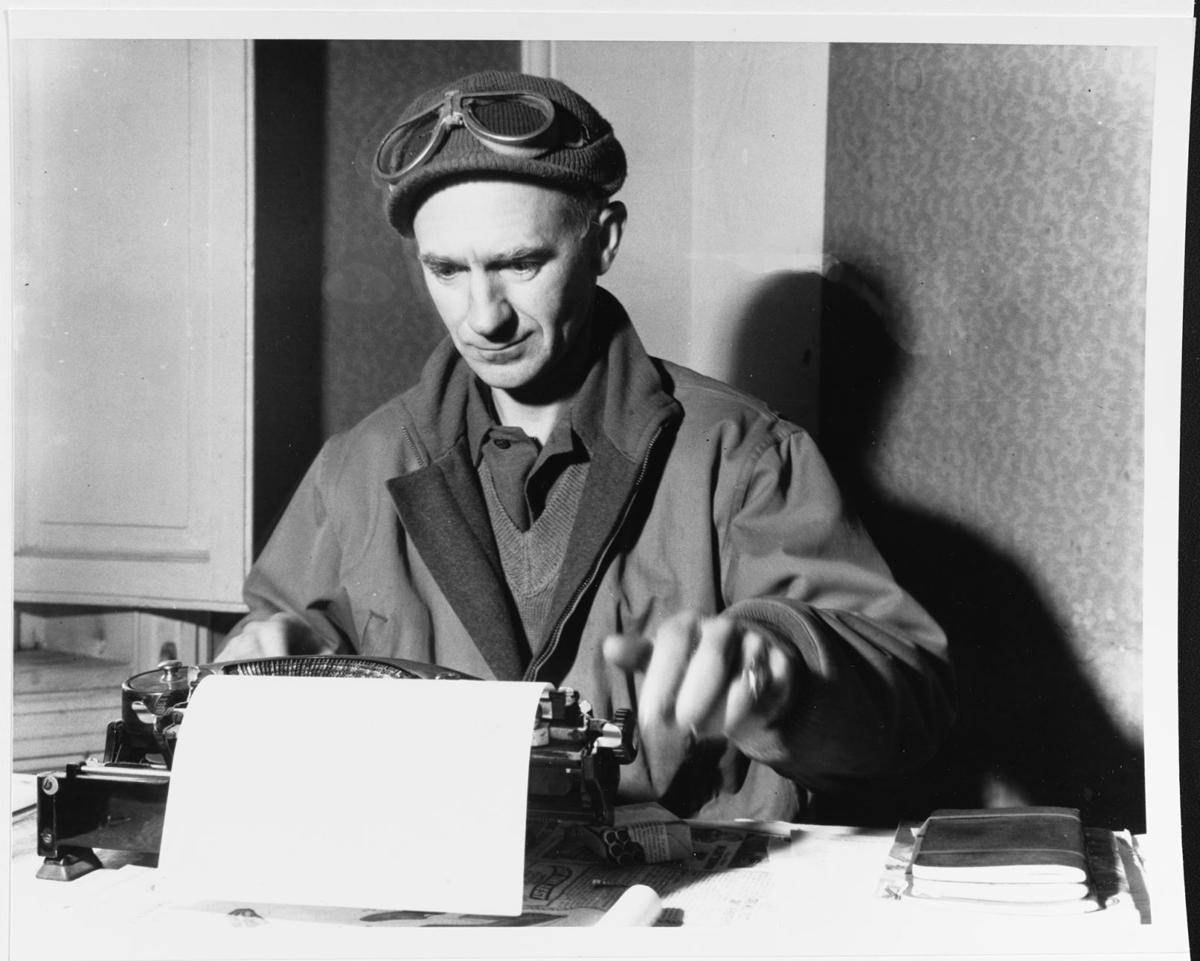

Ernie Pyle: America’s Eyewitness to War

Unquestionably the most famous and beloved American war correspondent of WWII, Ernie Pyle’s distinctive, folksy writing style brought the horrors of war into living rooms throughout the United States.

Embedded with front line troops in the European Theater of Operations from 1942 to 1944, Pyle wrote about ordinary “dogface” infantry soldiers, which he called the underdogs of World War Two.

Through his heroic reporting, Pyle became friends with enlisted men and officers alike, as well as war leaders such as Omar Bradley and Dwight D. Eisenhower. After returning stateside to shake off a severe case of battle fatigue, Pyle returned to the trenches in 1945, this time in the Pacific Theater of Operations.

Reinforcing his status as the dogface GI’s best friend, Pyle wrote a column from Italy in 1944, proposing that soldiers in combat should get “fight pay,” just as airmen received “flight pay.” In May 1944, Congress passed a law that became known as the Ernie Pyle bill, authorizing 50% extra pay for combat service.

Syndicated in over 400 daily and 300 weekly newspapers, his most famous column was The Death of Captain Waskow, when he was reporting from Anzio during the invasion of Italy.

“I don’t know who that first dead man was,” he wrote. “You feel small in the presence of dead men, and ashamed at being alive, and you don’t ask silly questions.”

He further wrote that as dead soldiers were brought down a mountain from the front lines, one of them that was laid out in the dim moonlight was much-beloved Captain Henry Waskow of the 36th Infantry Division.

Pyle wrote, “Then a soldier came and stood beside the officer, and bent over, and he too spoke to his dead captain, not in a whisper but awfully tenderly, and he said, “I sure am sorry, sir.” Then the first man squatted down and he reached down and took the dead man’s hand, and he sat there for a full five minutes, holding the dead hand in his own and looking intently into the dead face, and he never uttered a sound all the time he sat there. And finally he put the hand down, and then reached up and gently straightened the points of the captain’s shirt collar, and then he sort of rearranged the tattered edges of his uniform around the wound. And then he got up and walked away down the road in the moonlight, all alone.

Ernie Pyle’s Death

When Pyle was killed during the Battle of Okinawa, April 14, 1945, President Harry S. Truman said of gutsy reporter, “No man in this war has so well told the story of the American fighting man as American fighting men wanted it told. He deserves the gratitude of all his countrymen.” Pyle’s wife, Jerry, would die later that same year, from complications of influenza.