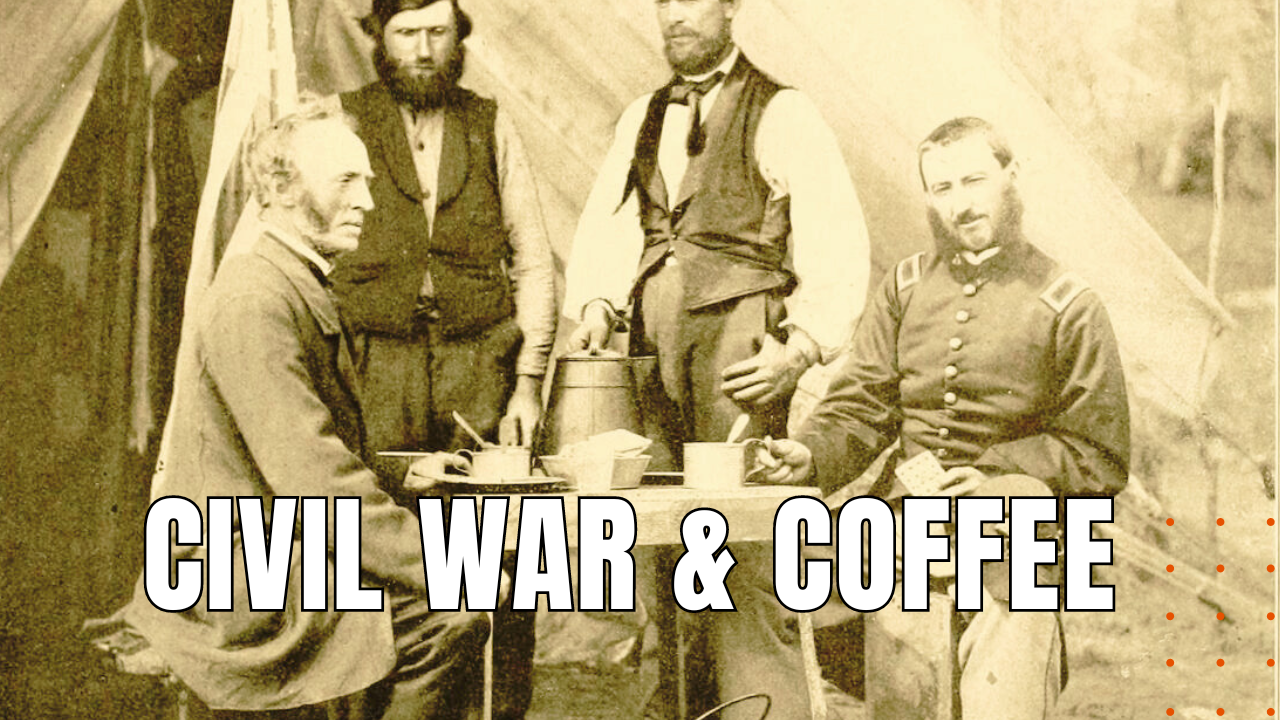

Coffee’s Impact on the Civil War

After New England patriots tossed British tea into Boston Harbor on December 16th, 1773, Colonial Americans boycotted the colonies’ once cherished beverage as a sign of loyalty to the cause of independence from British rule. In response, after America’s victory in the Revolutionary War, by 1830, coffee consumption had outstripped tea consumption by five to one, leading Andrew Jackson to replace army alcohol rations with coffee in 1832, with the underlying hope of energizing the nation’s soldiers, while reducing the all-too-frequent likelihood of drunken insubordination.

Growing Popularity

By 1860, Americans annually consumed a whopping six pounds of coffee per man, woman and child, consuming twice as much coffee as they had 30 years earlier, prompting Union General Benjamin Butler to press his subordinates on coffee’s equal importance to gunpowder, writing, “If your men get their coffee early in the morning, you can hold (your position).” With the outbreak of war, however, the increased demand for coffee became severely jeopardized by the Union’s own blockade on Southern ports, plummeting coffee imports from Java, Ethiopia, Haiti and Brazil, which in turn sparked coffee shortages for Union soldiers and northern abolitionists alike. The answer came in the form of future Liberian president Stephen Allen Benson, who emigrated to Liberia from Maryland in an effort to escape racial prejudice pandemic in the United States. Partnering with George W. Taylor’s “Free Labor Warehouse” in 1848, Benson imported 1,500 pounds of coffee into Philadelphia from his ever-expanding coffee growing interests in Liberia, which soon became a hit with northern abolitionists intent on boycotting products made by Southern slaves.

A Visible Advantage

By 1862, after President Abraham Lincoln formally recognized Liberia as a republic, Liberian coffee growers soon supplied the coffee needs of the Union Army and its resultant morale boost on the battlefield, while the Union’s blockade of Southern ports made both coffee and Confederate morale such a dire crisis that some historians suggest may have weakened rebel resolve on the battlefield and ultimately led to the South’s defeat. Confederate soldiers were reduced to brewing nauseating substitutes such as acorn grounds and sweet potatoes, while the north’s ready supply of coffee developed lifelong post-war habits among Civil War veterans that raised U.S. consumption of coffee to eleven pounds per person per year by 1885, making the lowly coffee bean, a key determinant to the outcome of the Civil War.