Carpetbaggers and Scalawags

After the American Civil War, by late 1866, Radical Republicans took control over Reconstruction policies in the South, passing the Reconstruction Act of 1867, while forcing southern lawmakers to ratify the 14th Amendment, which broadened the definitions of civil rights for African Americans.

What are Carpetbaggers?

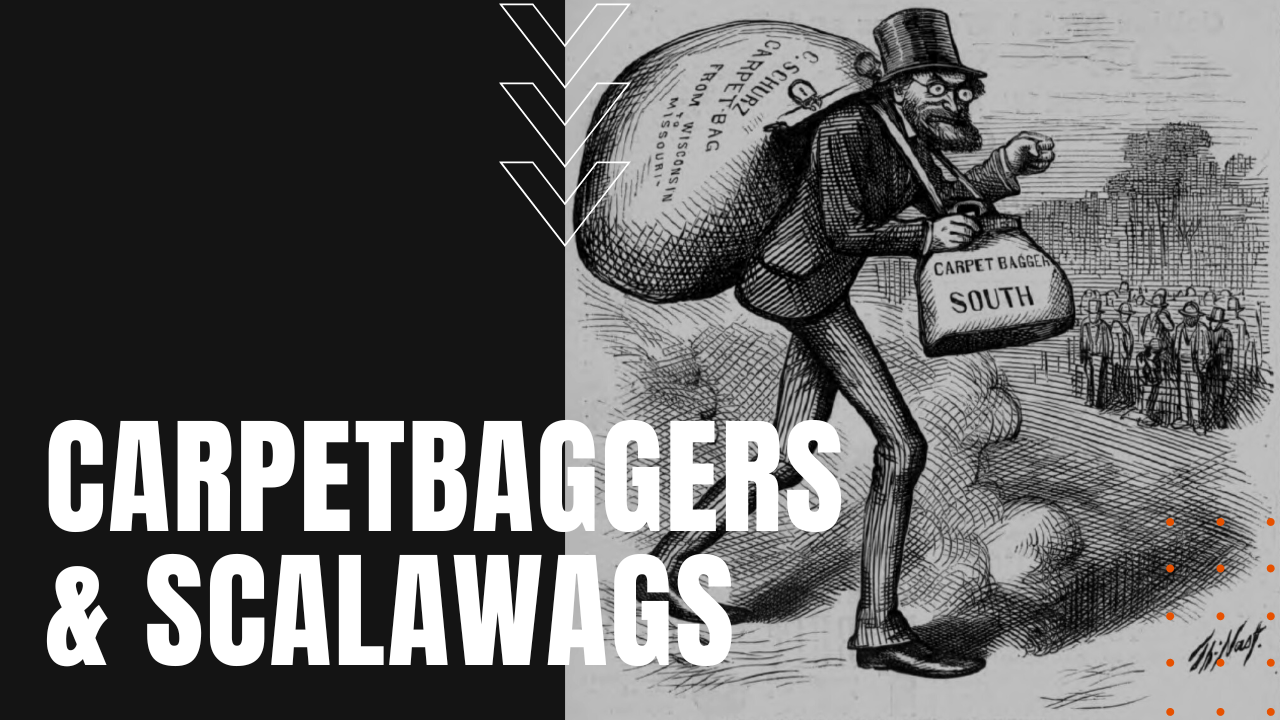

Known as carpetbaggers, a fair number of both opportunistic and well-intentioned northerners moved into the southern states to purchase, lease or partner with planters now stripped of their enslaved labor force, many hoping to make money from cotton.

In the beginning, many southerners saw carpetbaggers in a good light, hoping northern capital and knowhow could help recover a collapsed southern bloc economy. While many carpetbaggers came south with good intentions, working as teachers and businessmen, over time, well-intentioned carpetbaggers were cast together with the corrupt ones, creating a stereotype that all carpetbaggers were opportunistic interlopers who sought to grow wealthy on the South’s misfortune.

Scalawags of the South

For the nearly twenty percent of southerners who supported the Republican Party and felt that whites should recognize African American civil and political rights, to their majority southern opponents, southern white Republicans were labeled as scalawags for supporting northern interference into the old ways of old South.

Many scalawags were former conservatives from the now-defunct Whig Party, made up primarily of non-slaveholding small farmers, merchants and professionals, and while many hailed from the northernmost states in the Southern bloc, scalawags in particular wanted to keep the rebel element from re-establishing power in the postwar South, at the same time seeking the survival of small farmers saddled with near insurmountable debt.

The Southern Status Quo Upheld

By 1874, after an economic depression plunged the South into widespread poverty, support for Reconstruction began to evaporate, leading to the Compromise of 1877, when losing presidential candidate Rutherford B. Hayes was handed the White House, in return for an end to Reconstruction in the postwar South.

The backroom deal with southern legislators would see a robust return to segregation and Black Codes in the Jim Crow South for nearly a century more, until federal legislation and the civil rights movement of the 1960s brought an end to one of the longest inequalities in American history.