The Caning of Charles Sumner

During a time of westward expansion and manifest destiny—as territories vied for statehood one after the next—the issue of what new states would allow or disallow slavery grew evermore contentious in the chambers of Congress. As tensions mounted, Congress applied multiple bandaid acts in an attempt to keep a nation from fracturing, including the Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act of that same year, followed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which led to border wars known as Bleeding Kansas, when abolitionists and pro-slavery advocates in the Kansas Territory and beyond engaged in violent conflicts that erupted sporadically until 1859.

A Two Day Speech

During the ongoing debate in both houses of Congress, on May 19th and 20th of 1856, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner—A Free Soil Party member who abandoned the Whigs after their nomination of slaveholding southerner Zachary Taylor as their party candidate for president—delivered a two-day manifesto against the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which he described as, “the rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of Slavery.” Pointing a finger directly at the bill’s authors, Andrew P. Butler and Stephen Douglas, of Butler, Sumner said that “Of course, he has chosen a mistress… who, though ugly to others is always lovely to him, though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight; I mean the harlot Slavery.”

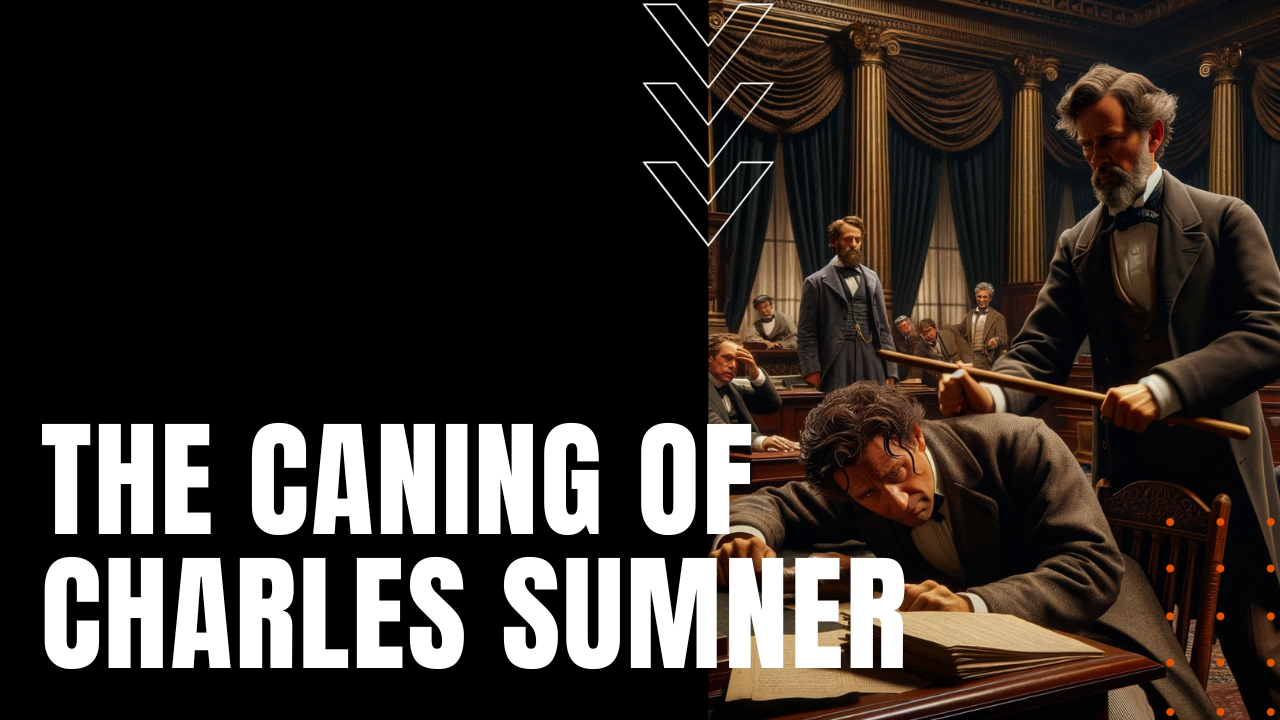

Violence Within the Capital

Deeming Sumner’s entire speech to be an incendiary condemnation of his beloved homeland, South Carolina Congressman Preston S. Brooks vowed revenge against Sumner’s egregious offense. Forced to walk with a cane after injuries sustained in a duel of honor, Brooks deemed Sumner unworthy of a duel—a southern gentleman’s highest act of chivalry—instead beating Sumner with his cane as the senator sat behind his desk, while two other southern senators prevented others from intervening. Following his near death beating, which forced Sumner’s absence from the Senate for the next three years to come, newspaper headlines that followed were evenly split along pro and anti-slavery lines. “A cowardly assault,” wrote the Hartford Courant, while an Alabama newspaper wrote that Sumner had it coming since his first day in the Senate chamber, making the caning of Charles Sumner, a violent foreshadowing of the war years to come.