Battle of Atlanta

Confident that the Confederate Army would lose a war of attrition, in the spring of 1864, U.S. Army commander, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, ordered five simultaneous offensives into the South, intended to break already weakened Confederate forces along their protracted frontier.

Sherman Leads Union Army to Atlanta

Grant assigned his friend Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman to command the fifth advance against Gen. Joseph E. Johnson’s Atlanta-based Confederate Army, in defense of the South’s largest industrial, logistical and administrative center outside of Richmond.

With Union forces closing in on Atlanta, a frustrated President Jefferson Davis relieved Johnston of command due to his lack of aggressiveness against Sherman’s army, replacing him with Lt. Gen. John B. Hood on July 18th, who in turn launched two attacks against Sherman—a July 20th offensive at Peach Tree Creek, and what would become known as the Battle of Atlanta.

The Battle of Atlanta

On July 22nd, Hood ordered a three-prong advance on Sherman’s forces—General William J. Hardee’s men to the Union’s left flank, Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalrymen to Sherman’s rear supply line, while General Benjamin Cheatham’s men drove straight into Sherman’s front line.

As the battle ensued, General James B. McPherson, in command of the Army of the Tennessee and a personal favorite of both Sherman and Grant, was shot and killed by Confederate forces in his push to the front line, making him the second-highest-ranking Union officer to perish in battle during the entirety of the Civil War.

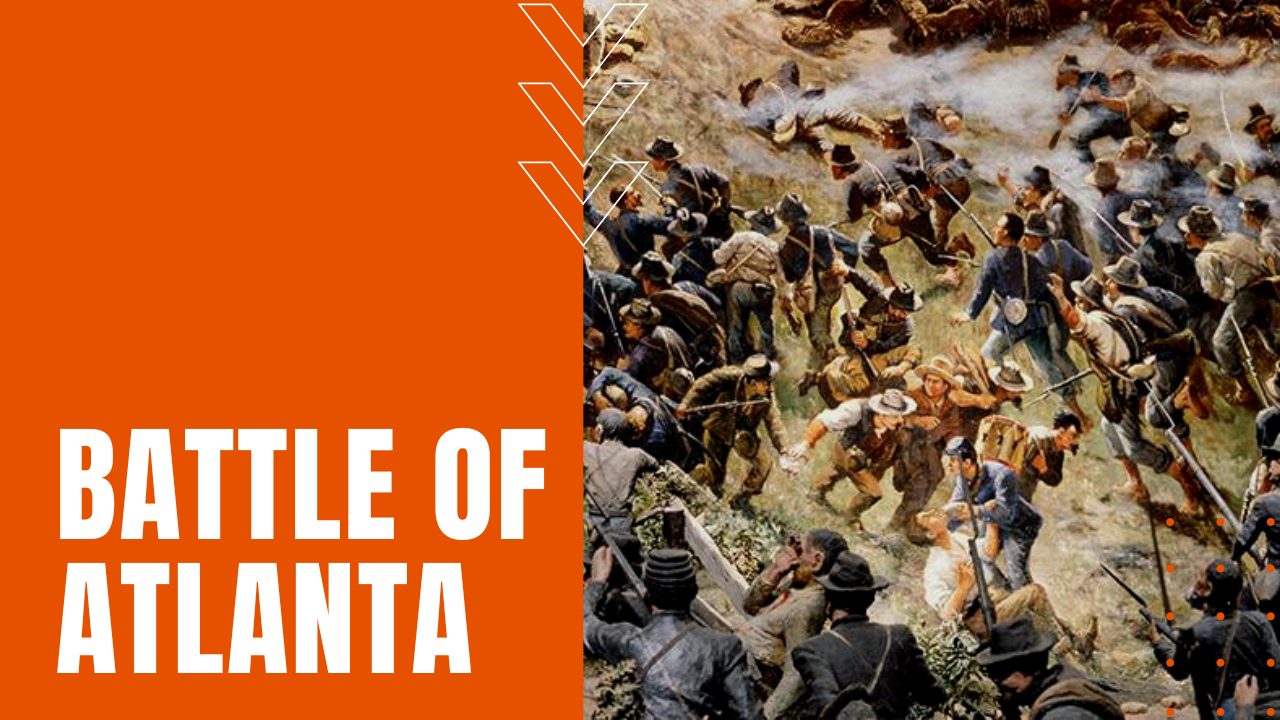

After all three prongs of Hood’s offensive ended in defeat and fallback, the main battle lines now formed an L shape, with the heaviest fighting centered east of Atlanta at Bald Hill, which during the day devolved repeatedly into bloody hand-to-hand combat, until the Confederates retired to the south just after nightfall.

Who Won The Battle of Atlanta?

The one-day battle witnessed 3,400 Union casualties, while the already depleted and dispirited Confederacy saw 5,500, leading to the Union Army’s Siege of Atlanta, until the city’s fall and capture on September 2nd, 1864.

The capture of the Rebel’s second most valuable stronghold did much to boost Northern morale and resolve, at the same time cementing President Abraham Lincoln’s second-term victory in November, making the Battle of Atlanta, an important inflection point in the South’s eventual surrender seven months later.