Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798

In 1794, when Federalist President George Washington signed a proclamation of neutrality during a war between England and France, the Jay Treaty would improve relations with England while angering the French.

When James Monroe and two other diplomats sailed to France to negotiate for peace, French politicians known as XYZ demanded a bribe before negotiations could begin, which infuriated the young American republic to no end.

Four New Laws Known as Alien and Sedition Acts

By the time John Adams was sworn in as the second U.S. president in 1796, France had seized more than 300 American ships, leading many to believe or insist that war with France was eminent and unavoidable. Amid mounting fears of enemy spies infiltrating American society, the majority Federalist Party, who supported a strong central government, prevailed over the minority Republican or Jeffersonian Party in passing four new laws, which collectively became known as the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Since many recent immigrants and new citizens favored the Republicans and their insistence that power remain with the individual states, Congress passed the Naturalization Act, which increased residency requirements for U.S. citizenship from five years to fourteen.

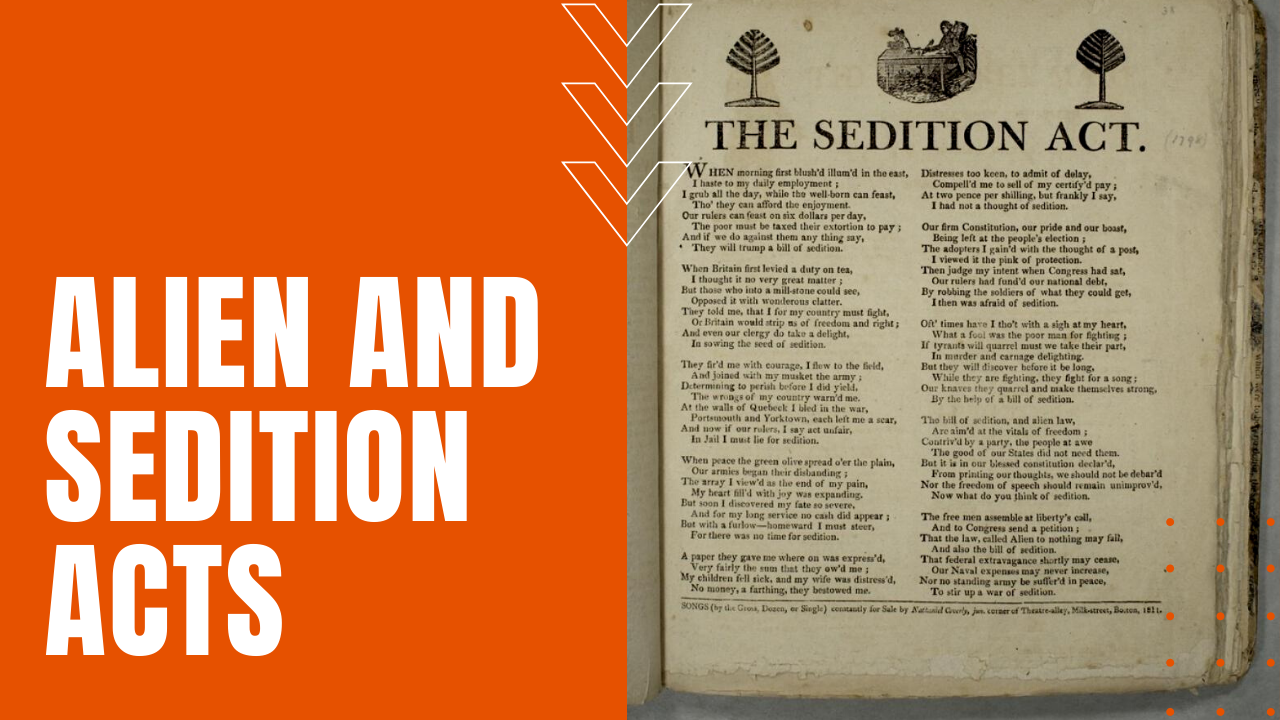

The Alien Enemies Act went on to permit the government to arrest and deport all males citizens of enemy nations in the event of war, while the Alien Friends Act allowed the president to deport any non-citizen suspected of plotting against the government, even if the country was not at war. The Sedition Act, on the other hand, took direct aim at anyone who spoke ill against President Adams or the Federalist-dominated government, effectively muzzling descent from the Republican side of the aisle.

Why Were the Alien and Sedition Acts Controversial?

While Republican lawmakers complained that the Sedition Act violated the First Amendment freedom of speech clause in the Constitution, the Federalists pushed the bill through Congress, which was signed into law by Adams on July 14th, 1798, with an expiration date set for March 3, 1801, which was the last day of his term of office.

By the law’s expiration, U.S. federal courts prosecuted no less than 26 individuals under the Sedition Act—nearly all of them editors of Republican newspapers who opposed the Adams administration.

The prosecutions fueled fierce debate over the definition and meaning of a free press, as well as the rights that should be afforded to political opposition parties in the United States.

In the end, widespread anger over the Alien and Sedition Acts fueled Jefferson’s victory over Adams in the bitterly contested presidential election of 1800, while their passage would go down in history as one of the biggest mistakes of the Adams presidency. By 1802, all of the Alien and Sedition Acts had either expired or been repealed, save for the Alien Enemies Act, which was amended by Congress in 1918 to include women.