The Capture of New Orleans

Roughly one year into the American Civil War, the Confederate’s control of the Mississippi River remained one of their most vital supply routes, as well as an important hub of Confederate industry and trade.

Fearing a Yankee invasion from the river’s northern flank, Southern war planners wrongly decided to concentrate their forces in northern Mississippi and western Tennessee, dispatching eight Rebel gunboats from New Orleans to cut off a potential Union naval attack above Memphis, leaving just 3,000 soldiers, two half-built ironclads and a handful of warships behind in defense of New Orleans.

Union Army Invades New Orleans

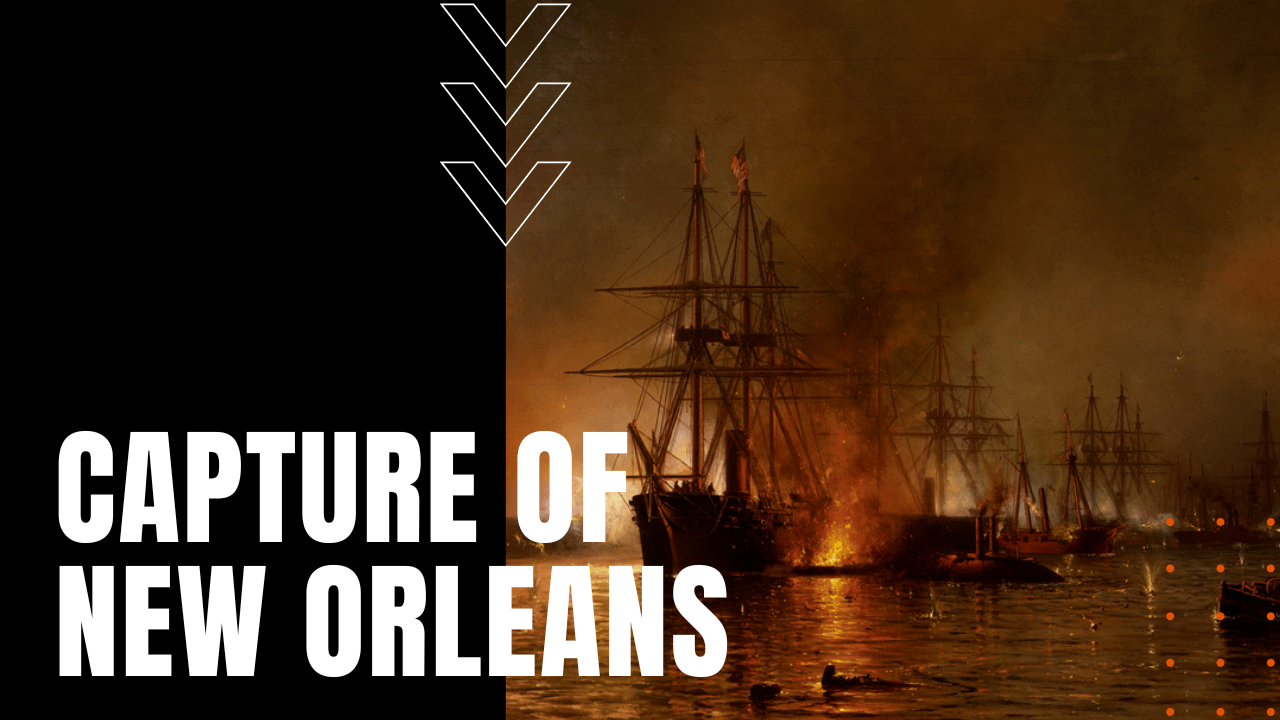

Instead, under the cover of darkness on April 24th, 1862, U.S. Admiral David Farragut led a fleet of 24 gunboats, 19 mortar boats and 15,000 soldiers past Fort Jackson and Fort St. Phillip, the city’s primary defensive fortifications against a Union assault from the Gulf of Mexico, sinking eight confederate warships before sunrise the following morning.

Confederates Surrender New Orleans

Realizing Confederate war leaders had made an egregious miscalculation regarding the defense of New Orleans and a southernly approach to the Mississippi River, Confederate General Mansfield Lovell surveyed the Union’s overwhelming naval force, convincing Mayor John Monroe that any resistance shy of total surrender would lead to a devastating bombardment of the city, pulling his forces out of New Orleans before Yankee soldiers began pouring into the city on April 25th.

Four days later, the last holdouts at Forts Jackson and St. Phillip surrendered to the Union navy, making the fall of New Orleans, one of the most impactful early losses to the Confederate cause.