Weimar Republic: Mutiny, Hyperinflation and Nationalism

After Germany’s defeat in the First World War, German sailors and soldiers mutinied against Kaiser Wilhelm the 2nd, forcing his abdication on November 9th, 1918. The next day, a provisional government was cobbled together between members of the Social Democratic Party and the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany, effectively shifting power away from the German military.

What Happened to the Weimar Republic?

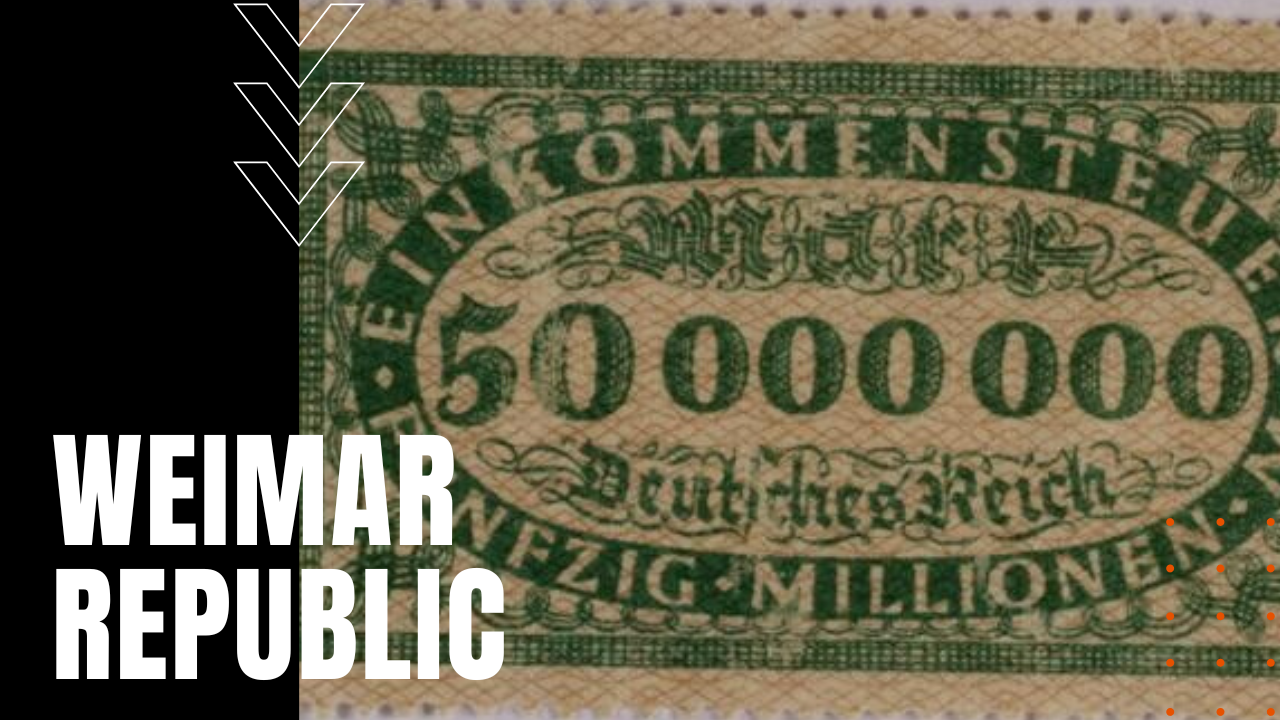

A new constitution was drafted in the city of Weimar, giving hope to a war-weary people, until stiff reparations outlined in the Treaty of Versailles crippled the German economy when the Weimar government was unable to pay their debts to foreign powers.

Printing more currency to shore up the devalued German Mark, a period of staggering high inflation crippled the middle class, ironically ushering in the Golden Twenties of Germany, when hyperinflation led Germans into nightclubs and bars, in the hopes of spending their daily wages before their money lost value the next day.

Dawes’ Plan

During the 100-day chancellorship of Gustav Stresemann, that same year, the League of Nations asked U.S. banker Charles Dawes to grapple with Germany’s insolvency and hyperinflation, resulting in the “Dawes Plan,” which set up sliding scale reparation payments based on a strengthening GDP, which in turn stabilized the Weimar Republic and energized the German economy.

After Germany was finally allowed into the League of Nations, Germany’s improving relationships with her wartime enemies opened the door for increased international trade, further strengthening the German economy. Following the stock market crash of 1929, America’s financial disaster and subsequent Great Depression had a ripple effect across global economies, including a second devastating collapse of the newly recovered Weimar Republic, hurling Germany backwards into insolvency, business failures and high unemployment.

Hitler’s Rise To Power

Despite Adolph Hitler’s failed Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, after the ravishes of a second economic turndown since the end of World War One, in 1932, Hitler’s far right Nazi Party appealed to many downtrodden Germans, quickly establishing the Nazis as the largest political party in German Parliament.

In January of 1933, Hitler was named chancellor of Germany, which would soon devolve into a dictatorship devoid of parliamentary checks and balances, allowing a solitary man to thrust Europe and eventually America into the dark days of World War Two.