Early American Imperialism

“From the time the first settlers arrived in Virginia from England and started moving westward,” writes Yale historian Paul Kennedy, “this was an imperial nation, a conquering nation,” while Ben Franklin wrote that:

“Hence the Prince that acquires new territory, if he finds it vacant, or removes the Natives to give his own people room.”

Benjamin Franklin

European-American Expansion

Combined with the Indian Wars and the ethnic cleansing campaign known as Indian Removal, European-American settlers embraced a policy of imperialism from the moment they set foot in North America, and while President George Washington enacted a policy of non-interventionism that lasted into the early 19th century, the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 drew a line in the sand, declaring North America off-limits to further European colonization, which in turn gave rise to the national drive of Manifest Destiny, announcing an open season for westward expansion toward the Pacific Ocean.

While President Thomas Jefferson negotiated the 828,000 square-mile Louisiana Purchase from Napoleonic France, an additional 525,000 square miles was added by force after the United States’ victory in the Mexican-American War of 1846, leading then-Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, to proclaim at the onset of hostilities that

“I should welcome almost any war, for I think this country needs one.”

Teddy Roosevelt

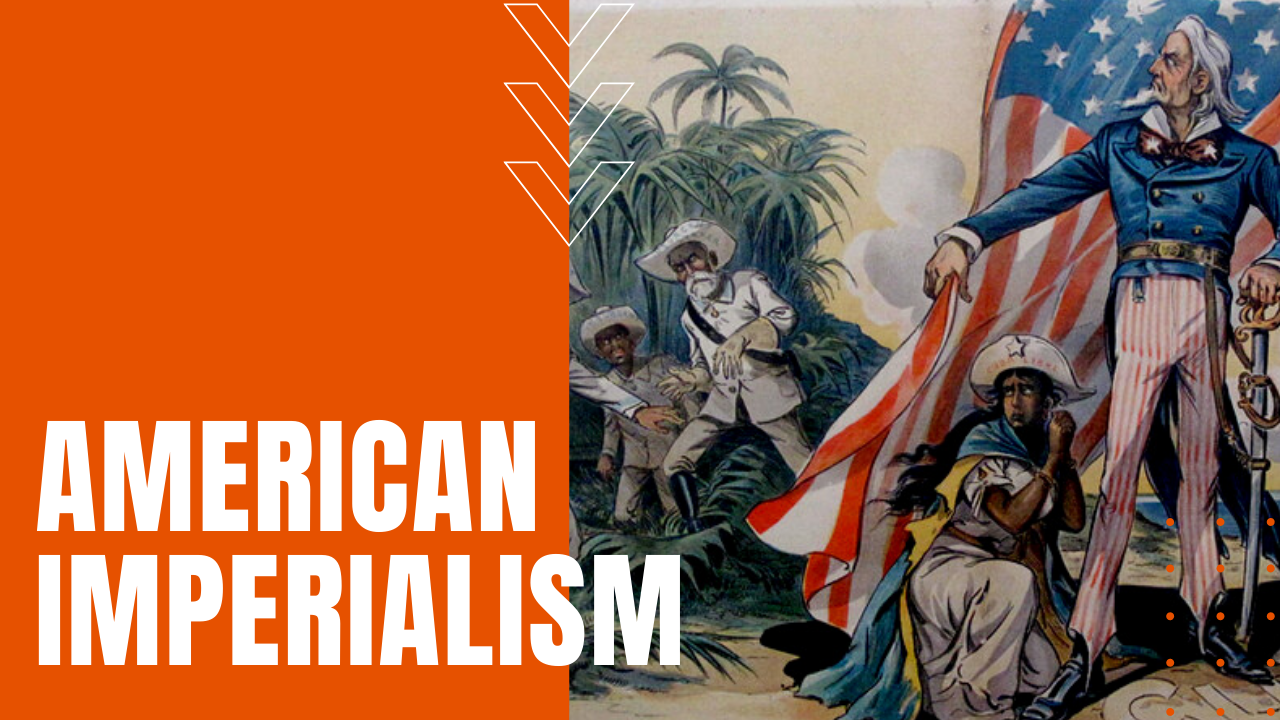

American Imperialism Abroad

While others like Senator Sam Houston of Texas proposed the annexation of Mexico, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras and San Salvador, such expansionist sentiment was put into action by physician, lawyer, journalist and mercenary William Walker, who launched a privately-funded occupation of Nicaragua in 1855, until he and his paid mercenaries were ejected from the country by a coalition of Central American armies.

But perhaps the biggest proponent of New Imperialism was President Theodore Roosevelt and his Big Stick Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, where he successfully acquired or annexed Spain’s remaining island colonies of Puerto Rico, Cuba, Guam, the Philippines and Hawaii, following the brief yet decisive American victory in the Spanish-American War of 1898.

Critics of 19th Century American Imperialism

While late 19th century American Imperialism was met with criticism by many at the time, American politicians justified foreign land grabs as protecting and expanding markets for American products, at the same time spreading the virtues of American democratic governance and Christian values. The period was also seen as a natural offshoot of what historian John Fiske called Anglo-Saxon racial superiority, or what Rudyard Kipling poetically called “The White Man’s Burden,” all the while supported by America’s open embrace of Social Darwinism and Manifest Destiny.