Imperialism in China: Trade, War, Nationalism and Rebellion

After Qing Dynasty leaders attempted to limit western influence by establishing the Canton System, which forced all foreign merchants to trade only in the port of Canton—now known as Guangzhou—during the Age of Imperialism, such restrictions resulted in rising tension between China and her oftentimes bullying trading partners from Britain, France, Russia, Germany and Japan.

Opium Wars and More

During imperialism’s peak in the 19th century, Britain in particular traded heavily in China for the much-coveted commodities of tea, silks and porcelain, but since the British lacked sufficient silver to affect purely monetary transactions, they traded heavily in opium instead, creating generations of addicted Chinese, while ushering in long periods of civil unrest in Chinese society.

China’s pushback against the British resulted in the First Opium War of 1839 to 1842 and the Second Opium War of 1856 to 1860—two back-to-back losses for China that led to the “unequal treaties” that opened up further trading rights for western powers, as well as rising foreign influence in the once isolationist nation.

China’s weakening hand saw the rise of outside “spheres of influence” in China after the mid-1800s, allowing the Russians to take control of a large portion of Northern China, while the Japanese severed Chinese dominance over Korea, which led to yet another crushing defeat for the Qing Dynasty in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894 to 1895, which forced China to hand over control of Korea, the island of Taiwan and the Liaodong Peninsula.

Chinese Nationalism and Boxer Rebellion

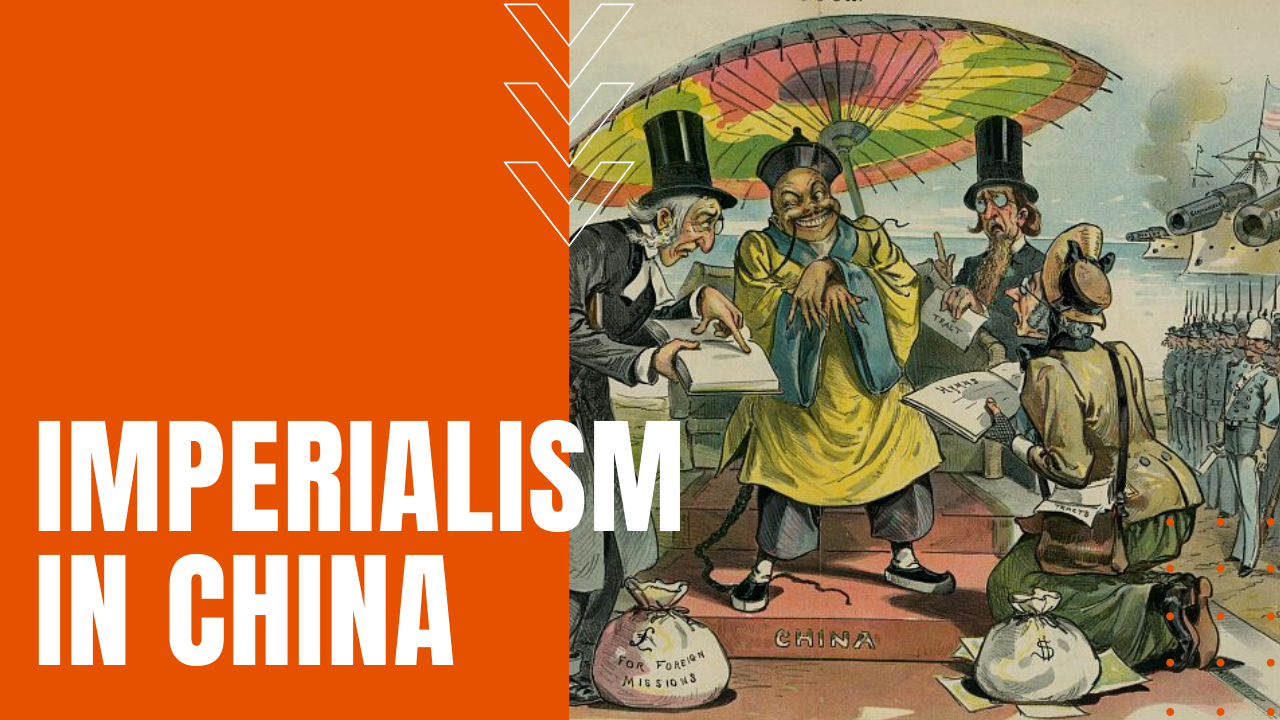

For its part, while the United States made no regional claims on China, it insisted on an “open-door policy,” which called for equal access to trade in China for all nations. After centuries of western influence in China, a wave of nationalism arose near the end of the 19th century, leading to the Boxer Rebellion of 1899 to 1901, which sought to end western imperialism in China, as well as the ousting of Christian missionaries from their land.

As the rebellion spread, Qing Empress Dowager Cixi declared war on all foreign nations with diplomatic ties to China, leading to an eight-nation force of some 20,000 troops who crushed the rebellion in 1901. In keeping with China’s bad luck pushback against foreign invaders, China signed the Boxer Protocol on September 7th of that same year, which saw the destruction of military fortifications surrounding Beijing, a two-year prohibition on arms imports and a payment of $330 million in reparations to the foreign powers that ended the rebellion, making imperialism in China, a symbiotic yet unwanted remnant in near Chinese history.