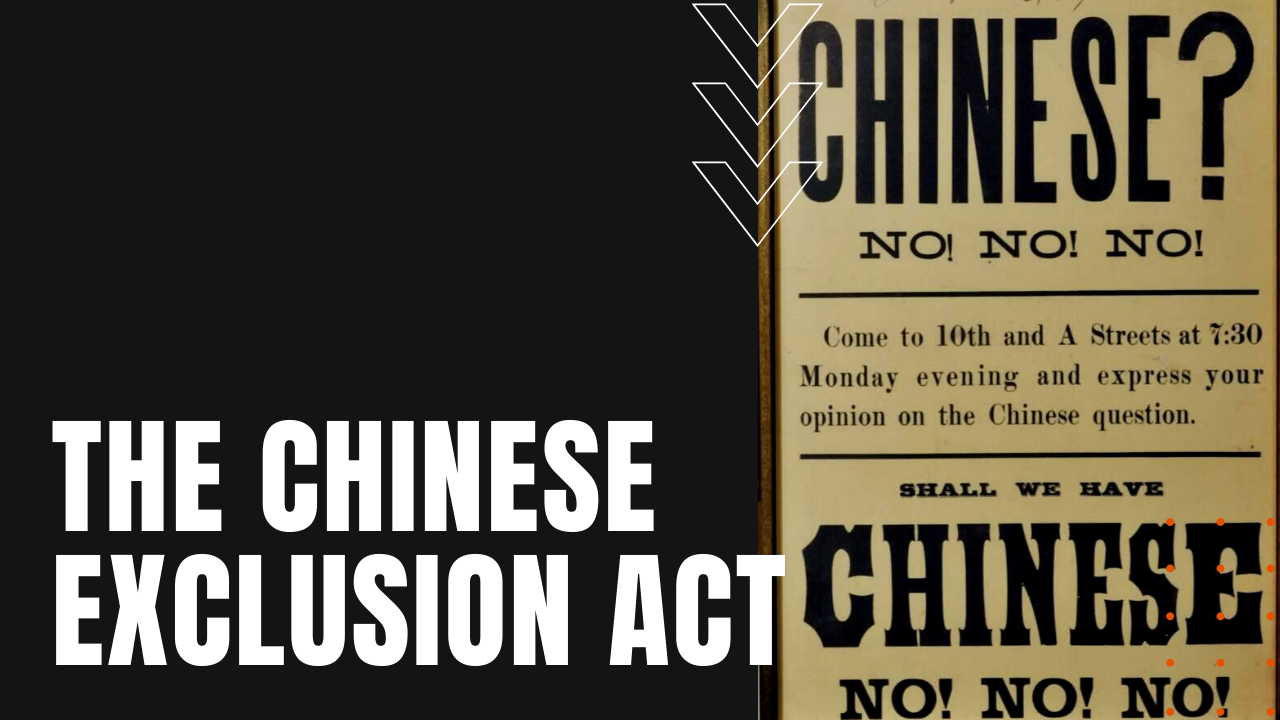

Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

Following the Opium Wars against Great Britain, China’s crushing war debt combined with a protracted stretch of floods and droughts left many Chinese peasants seeking new opportunities abroad. Many Chinese found their way into California after James Wilson Marshall’s 1848 discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill.

What Led To The Passage Of The Chinese Exclusion Act?

Combined with another devastating crop failure in China, some 20,000 Chinese immigrants passed through San Francisco’s customs house in 1852 (up from 2,716 the previous year), igniting a racially charged spree of violence by whites, who saw the Chinese as a threat to their ongoing ability to earn a living wage.

Later that same year, in an effort to curb the violence and allay the fears of white miners, California imposed a Foreign Miners Tax of $3 a month, despite the fact that Chinese laborers worked for less money and longer hours than whites, oftentimes given the most dangerous and backbreaking roles in a given mining operation.

To worsen the plight of Chinese immigrants, the 1854 Supreme Court Case of People v. Hall ruled that the Chinese—like African Americans and Native Americans before them—were no longer allowed to testify in an American courtroom, further limiting their ability to seek justice against the rising flood of white-inspired violence.

During construction of the first transcontinental railroad, after Charles Crocker and other founders of the Central & Southern Pacific Railroads placed employment ads for white workers, when only a few hundred white men applied, Crocker began hiring less expensive Chinese workers to fill the labor vacuum. Before the tracks came together at Promontory Point Utah on May 10th, 1869, some 15 to 20,000 Chinese laborers had almost singlehandedly built one of the greatest engineering achievements in American history, working from sunup to sundown six days a week, all for $26 a month.

Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

Signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on May the 6th, 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act furthered the nation’s racist tenor by suspending all Chinese immigration for a ten year period, at the same time excluding Chinese-Americans already in the country from seeking naturalization as a U.S. citizen, and while Chinese-Americans challenged the constitutionality of the law in court, all of their efforts failed to bring about justice.

The immigration ban was extended an additional ten years thanks to The Geary Act of 1892, followed by the Immigration Act of 1924, which extended the nation’s exclusionary practices to not only the Chinese, but other “undesirable” groups such as Hindus, Middle Easterners and the Japanese. Chinese immigration into the U.S. plummeted as a result, until the Magnuson Act of 1943 at long last made Chinese-Americans eligible for U.S. citizenship.