Hoovervilles of the Great Depression

At the height of the Great Depression, when one in four eligible workers found themselves homeless and unemployed, hundreds of shantytown slums sprang up across the nation, housing hundreds of thousands of destitute Americans.

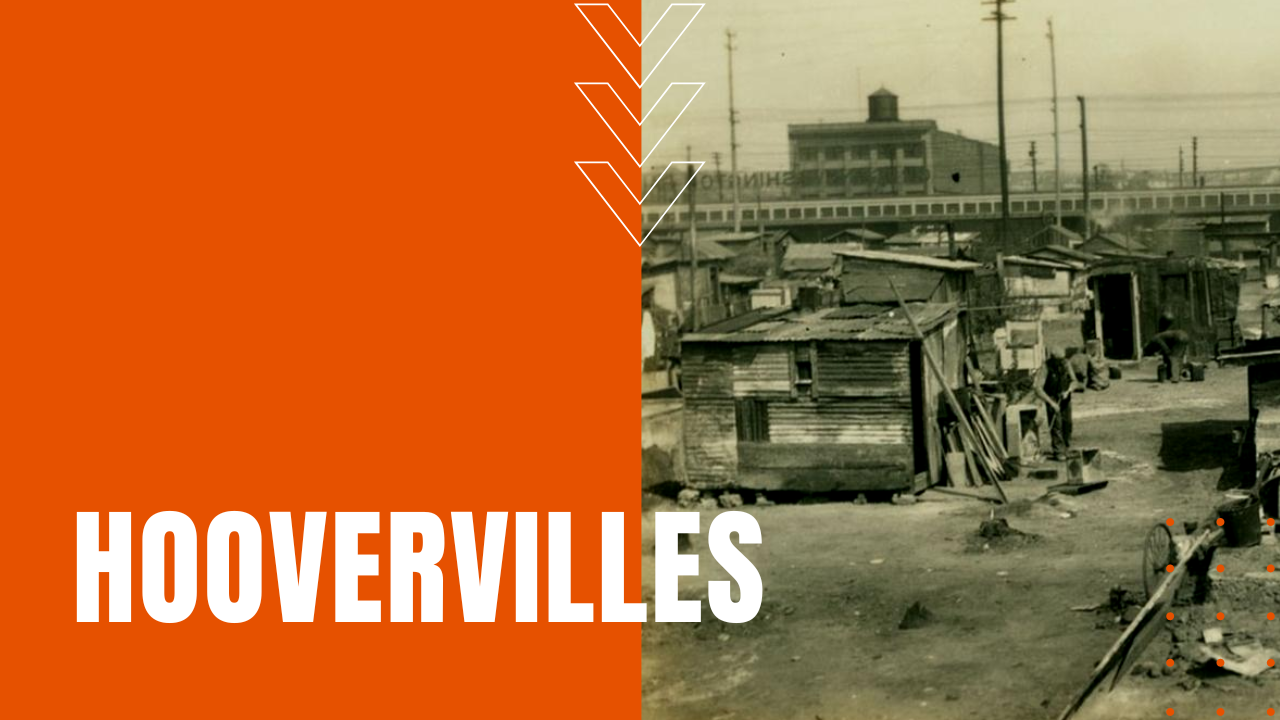

Hooverville Shantytowns

Disillusioned citizens called them Hoovervilles, referring to the commonly-held belief that Republican President Herbert Hoover was a do-nothing leader, who passed responsibility for the rampant homeless epidemic on to local governments and charities.

Homelessness was certainly present long before the Great Depression, making the condition a common sight in most American cities well before the Black Tuesday stock market crash of 1929. Most cities built municipal lodging houses for their homeless until the Great Depression exponentially increased demand for limited public housing.

As a result, massive Hoovervilles formed near soup kitchens, usually trespassing on private lands, yet tolerated or ignored out of dire necessity. Some Hooverville residents possessed construction skills, allowing them to build their houses out of stone, but the vast majority resorted to building their residences out of wood from crates, cardboard, scraps of metal or whatever materials they could find.

When a Hooverville formed near the Reservoir in New York’s Central Park, the residents were hastily evicted by the police. As the Depression wore on, however, public sentiment became more sympathetic, and in July 1931, a judge suspended the sentences of 22 unemployed men sleeping in Central Park, giving each of them two dollars out of his own pocket.

“We work hard to keep clean,” one of the men said to the judge, “because that’s important. I never lived like this before.”

In 1932, Democratic Presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt campaigned for the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid. After his election to the White House, at his direction, congress passed a series of emergency measures known as The New Deal for the American people, forging a new government agency known as the Works Progress Administration or WPA.

The program would grow to employ 8.5 million people and spend over 11 billion dollars as it transformed the nation’s infrastructure by putting Americans back to work.